Contrary to popular belief, the Mao suit did not originate as the de facto communist clothing in China. Its emergence during the Republican era (1912–1949) as the “Zhongshan suit,” named after Republican leader Sun Yat-sen, was strongly influenced by Chinese student uniforms and Japanese and Soviet military outfits.1 The Mao suit, featuring a high and turned-down collar and four buttoned pockets, signifies a cosmopolitan urge to distinguish itself from the side-fastening tradition of late imperial Chinese clothing.2 From the 1950s, as the Mao suit and its variants increasingly dominated the wardrobes in the People’s Republic of China (1949–), its appearance became synonymous with the arrival of a communist cadre.3

Born to anti-communist parents in British Hong Kong and working as an artist from Canada in New York in the 1980s, Tseng Kwong Chi (1950–1990) donned the Mao suit to stage and photograph identity performances that blur, and more crucially, question the boundary between perceived reality and staged fiction. His recognized works, including the East Meets West a.k.a. Expeditionary Self-Portrait Series (1979–1989) and the Costumes at the Met Series (1980), feature the Mao suit prominently.4 In these works, Tseng “infiltrates” and deconstructs public spaces under the guise of a self-named “ambiguous ambassador” connected with communist China, such as popular tourist destinations and the Met Gala. The role the Mao suit plays in aiding these parodically deconstructive performative acts has received attention from critics.5

The deconstructive readings, while indispensable for understanding Tseng’s work, often conceal other creative strategies, preferring clarity in militancy to understanding what I call a “distance of ambivalence” between the performance artist and his persona. In an essay that draws on the formal repetition of the Mao suit evident in Tseng’s photographs, Asian American studies scholar Warren Liu sharply identifies that the readings of Tseng’s work as deconstructive of the “Oriental other” stereotype “have become somewhat de rigueur, even if that context has been engagingly reframed under multiple rubrics.”6 Liu then goes on to argue that the multiplied and codified Mao suit can constitute a formal interpretive frame, away from the life narratives mentioned frequently in conjunction with Tseng’s work. Within the consideration of this essay, to maintain that Tseng’s work can act in defiance of the stereotypical values ascribed to him and his racialized existence is certainly a justifiable argument. This is because the mark of difference created at the junction of the Mao suit, Western landmarks, and the title of the series “East Meets West” is made hyperbolic and ripe for biographical and disidentificatory analysis.7 Yet, it is imperative to reengage with the performative-photographic work, acknowledging but working alternatively from the subversive readings of Tseng’s practice. Picking up on Liu’s divergent interest in Tseng’s photographic works allows the spectator to probe beyond the recurrent approach to analysis and locate other creative logics at work.

My argument in this essay is twofold. Firstly, I examine how the subversive interpretation of Tseng’s use of the Mao suit shapes the artist’s lauded reception. This examination of the reception is pivotal, as it unveils a retrospectively narrowed distance between a minority appearance and a conceptual activist core recognized by an insightful audience. Although this correlation is encouraging, it risks neglecting facets of the artist’s identity crucial to his practice. Concurrently, deviating from Liu’s argument which sets aside biographical interpretations to emphasize the conceptual repetitiveness of the Mao suit in photographs, my discussion maintains its foundation in Tseng’s self-referential performance—the “self” here encompasses Tseng as both a transnational artist and a racialized other. I contend that a distance of ambivalence between the identities informs Tseng’s appropriation of the Mao suit, shedding light on how Tseng’s adoption of the multivalent outfit remains heterogeneous to the minoritarian image he might project. This distance, when compared with other art projects that also construct and deconstruct identities through persona performance, introduces transnational perspectives to the interpretation of art made in the United States, challenging quick judgments about a queer diasporic artist of color.

Beyond the Smooth Infiltration: The Enduring Distance Between Tseng’s Rhetorical and Fictional Identities

The East Meets West Series consists of self-portraits placing Tseng in the Mao suit against iconic Western tourist locales. Despite the apparent ideological dissonance, tourists observing Tseng’s performance accept the communist guise as Tseng’s actual identity, which prompts them to interrogate the artist with curious questions.8 Similar scenarios occur during the production of the Costumes at the Met Series (fig. 1), where Tseng, donning the Mao suit, gains entry to the Qing dynasty–themed gala hosted by the Costume Institute as a press member of the now-defunct Soho Weekly News.9 In the resultant images, Tseng, alongside New York’s cultural, political, and economic luminaries—some attired in Chinese-inspired or orientalist fashion—joyfully poses with a cassette Dictaphone. In so far as Tseng is mistaken for an emissary or journalist from China, he interacts and poses with gala attendees, as seen in an image where Tseng appears to interview Andy Warhol and his entourage.

© Muna Tseng Dance Projects, New York. www.tsengkwongchi.com

In critical narratives that applaud Tseng’s performance as forays into normative public spaces, the Mao suit enables Tseng to convincingly present himself as the “ambiguous ambassador.” This persona then allows him to disidentify with the role—that is, to operate within yet resist the exclusionary and racist regimes of representation that eagerly orientalize him. Thus, by underlining the initial success and subsequent utility of the “infiltration,” such interpretations view the Mao suit as a tacit but potent tool for the artist. However, what is seldom scrutinized is the actual level of conviction and credibility that Tseng is intent on investing in the Maoist emissary/journalist façade. Here, the well-mentioned identification badge—emblazoned with “SlutForArt” and his mirrored-sunglassed headshot—worn with the Mao suit exemplifies Tseng’s deliberately flawed mimicry. Sporting this badge, Tseng’s presence in spaces typically closed to him, like the Costume Institute Benefit, is likely to attract skepticism or even outright challenges from gatekeepers.

Contrary to first assuming Tseng delivers a credible real-life performance, only to later elaborate on the mimicry’s (not so) clandestine insincerity—thereby superimposing and closing the distance between the façade and the conceptual strategy—I suggest that his performance exhibits a divided or internally discordant sense of identity from the onset. On one hand, borrowing from Bill T. Jones, choreographer and Tseng’s friend, Tseng lets the “blankness” expected of him to take hold and transforms into a “smooth surface” for others to project their fictional perceptions of his identity without arousing suspicion.10 On the other hand, Tseng’s rhetorical subjectivity as a performance artist, not confined to his assumed persona, occasionally emerges. The fictional and rhetorical identities tend not to be equally legible, as different viewers at different times perceive this performativity variously.11

The instances of “confusion” between the identities and their subsequent disentanglement are central to my inquiry into the distance between the artist’s identities. When the audience perceives Tseng’s performance as more than an attempt to covertly infiltrate social functions, the Mao suit surfaces as an object teeming with meanings, rather than a disguise concealing the artist’s rhetorical role and intent. In other words, recognizing the suit as something other than a mere tool for camouflage illuminates the discernible distance between Tseng and the facilitative role of the Mao suit in his infiltration.12 It was also Bill T. Jones who once characterized Tseng’s performance as “Chinese drag.”13 Drawing on the notion of “drag,” I propose that Tseng’s work is a vivid masquerade of diverse racial, national, and ideological expressions, and I will examine selected images from the East Meets West and Costumes at the Met Series, as well as a documentary on the East Meets West Series and a dance-theater tribute to the late Tseng. By juxtaposing the works with key biographical details that permeate Tseng’s self-implicating performance, I explore the insights into considering Tseng’s approach to the Mao suit as a case of creative appropriation. The scrutiny of the internal conflicts rattles the superficially stable semantics of the Mao suit and spotlights the act of appropriation as one that teases out the enduring distance between the artist and his chosen signifier, ultimately exposing transnational complexities and tensions beyond multiculturalist confines.

Political Commentaries, Performativity, and the Risk of Irrecognition: East Meets West Manifesto and Its Ambivalence

Tseng’s adoption of the Mao suit only ostensibly and momentarily facilitates his passage into a Chinese communist cadre. In 1989, Tseng penned an article titled “Cities” for the Japanese magazine Inside, introducing with text and images his East Meets West Series. He opens with an analytical recounting of his typical interactions with “real” tourists at his chosen sites:

It is not easy being a Chinese tourist. There are stares: a Red Guard on the loose? Then the questions: “Do you speak English?”; “Why do you wear that suit?”; “Parlez-vous français?”; “Where are you from?”; “Why do you wear that suit?” Should I tell them the truth, that I am actually a New York conceptual performance artist/photographer carrying on my lifetime art project of the East meeting the West. Or shall I really be a tourist from China. It is certainly more fun being a tourist with a camera.14

Christine Lombard’s 1984 documentary about the East Meets West Series confirms the onlookers’ intrigue, yet a sense of rehearsed preparation in either Tseng’s narration or the filmed interactions is apparent. Tseng, appearing both on-camera and as a voiceover, remarks: “When I work in the streets, people ask me what I do. Sometimes, I invite them to be in the picture with me.”15 Accompanying this commentary is a likely staged short scene: a passerby is drawn to Tseng, who is about to strike a pose before an equestrian statue, and Tseng invites her to join the photograph. Post-photo, they exchange a handshake—there is no further conversation or questioning. Calmness permeates Tseng’s voiceover, complementing the short but composed interaction between Tseng and the passerby. One would imagine a compact moment of what could be cultural stereotyping might be filled with frustrating inquiries and perturbation. However, like the calmness suggested by the period punctuation marks following the interrogative sentences in “Cities,” in the documentary, Tseng prioritizes a composed demeanor and projects an overly rehearsed act, even though he does not immediately reveal to his onlooking audience that he is, actually, not a traveler from communist China.

Pointing out the rehearsed quality in Tseng’s performance is not equivalent to suggesting that Tseng’s Maoist identity is merely a swift pretense, as if it is a persona that should appear or disappear easily depending on the presence or absence of the outfit. If there is a readily identifiable purpose with Tseng’s decision to delay only so slightly revealing his artist self, it is to poke fun at the rooted misconception of all Chinese as communists and contemporary China as a country definable by surveillance, dictatorship, and subjugation. This interpretation that builds on the temporariness of the credible performance is in line with the fact that Tseng resorts to a conceptualist calmness in explicating his communist camouflage, jointly gesturing towards geopolitically commentative underpinnings of the performance. In Lombard’s documentary, Tseng opens his narration by linking the East Meets West Series to Nixon’s televised 1972 visit to China, calling relations between the United States and China “official and superficial.”16 By foregrounding political conflicts and the ensuing diplomacy, the latter of which he perceives as empty, Tseng implicitly designates his satirical art to challenge late–Cold War national and international rhetorics.

East Meets West Manifesto (1983; fig. 2), an iconic and originary photograph of the East Meets West Series, also expresses this geopolitical concern. Wearing the Mao suit, Tseng positions himself at the center and between the US and PRC national flags, appearing physically as the “ambassador” he purports himself to be. Yet, the space depicted is also multilayered, and Tseng is about to draw up the US flag like a curtain, so he could walk from the visually flattened and cramped intermediate space between the PRC and US flags to the very front. His stance is steady and his face unsmiling, evoking the stereotypical stern-faced comrade while revealing a sense of determination because of the very sternness. Tseng might seem as if he is a determined communist cadre, but he is also, physically, and metaphorically, an in-between figure who is about to move, in an almost utopian resolute manner, beyond his intermediary position backed by communism and delimited by democratic capitalism.

Photo by Tseng Kwong Chi

© Muna Tseng Dance Projects, New York. www.tsengkwongchi.com

Despite Tseng’s efforts to unfold geopolitical tensions through appropriating the Mao suit, it remains necessary for me to again acknowledge his temporarily credible performance in public: the likelihood of Tseng being mistaken as a communist Chinese subject is high when he performs in public with the outfit. Asian American and visual culture studies scholar Sean Metzger lays out in detail in his book Chinese Looks: Fashion, Performance, Race the development of US perceptions of the Mao suit. Stating that “the Mao suit was never a stable signifier,” Metzger traces the history of the perceptions from the suit’s initial equivalence to the unsophisticated communist faction in China during the Chinese Civil War (1927–1950), to the suit’s later significance as a metonym for both communism and China during the Cold War.17 By the time Tseng performed in the Mao suit, there had been “a new contextualization of the Mao suit in American cultural production,” which Metzger explains as fueled by increasingly comedic portrayals of Mao as the Cold War dragged on.18 Nixon’s efforts to establish formal ties between the United States and China also contributed to the popularization of Mao paraphernalia, as the diplomatic visit was extensively documented and widely broadcast and reproduced.19 As one of the kitschy Mao paraphernalia, the Mao suit entered the North American commodity circuit. This entrance resulted in not only Tseng’s acquisition of the Mao suit at a Montréal thrift store, but also the onlookers’ ready recognition of Tseng as a Chinese communist traveler.20 However, given the uneven dynamic between the fictional and rhetorical identities, the onlookers’ recognition of Tseng as a Chinese communist is tantamount to their disregard for Tseng’s other identity: a gay male artist based in North America. To simultaneously recognize multiple identities of the artist, along with the distance of ambivalence between them, is an act that addresses the multifaceted Mao suit.

My analysis finds Tseng in this composite position that embodies political commentaries, performativity, and the risk of irrecognition, but as I have indicated in the section before, the ways in which this position is treated can vary. In that interpretation of this position, Tseng being taken as a Chinese communist traveler appears to exist in a causal relationship with the recognition of Tseng as a politically active gay male artist based in New York during the Reagan years and AIDS crisis. In other words, the initial dismissive irrecognition of Tseng—the incognito artist in the streets—has fed into a belated and somewhat vindicative understanding of him as a queer artist. This transformative interpretation that shrinks the distance between the seemingly norm-conforming performance and the activist figure can be observed in the analysis of Tseng’s performance as infiltration. Partly focusing on Tseng’s Costumes at the Met Series and premising his writing on José Esteban Muñoz’s theory of disidentification, Asian American and performance studies scholar Joshua Chambers-Letson suggests “that Tseng’s performance practice was a mode of minoritarian infiltration—a militant tactic geared towards surreptitiously entering into spaces and structures that one struggles to disrupt and even destroy.”21 By entering the Met Gala as an undercover artist pretending to be a communist journalist, only “to reveal the decadence, vulgarity, and shallowness of the elite sphere,” Tseng meets the criteria for managing minoritarian subversion.22 But is militancy truly so overwhelmingly characteristic of Tseng’s communist look? If we shift our attention back to the ambivalent but irreducible distance between the identities and further to Tseng’s always present rhetorical identity as an artist, we can situate his transnational concerns. Those concerns demonstrate a biographical side as well as the geopolitical side, existing alongside the artist’s better-known minoritarian, infiltrating mode.

Some background information about Tseng’s ways of life can help address the transnationality that the performance speaks to, as it offers a peek into the significatory distance that Tseng the artist finds between himself and his Maoist persona. Propelled by the communist triumph over Kuomintang in the Chinese Civil War, Tseng’s family moved from mainland China to Hong Kong, then a British colony. Tseng Kwong Chi was born Joseph Tseng in Hong Kong in 1950. Fearing the seemingly encroaching tumult of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the Tseng family moved again by the mid-1960s, this time to the white suburbs of Vancouver for a more stable North American middle-class lifestyle. As a young adult, Tseng moved from Vancouver to Montréal, Paris, and finally, New York. He had his father send him to study art in Paris at the École Supérieure d’Arts Graphiques after attending the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and Sir George Williams University in Montréal.23 Educated in English and French as well as bourgeois lifestyles and tastes, according to his sister Muna Tseng, “[he] was a snob, an aesthete, an intellectual, a spoiled rotten, first born, number one Chinese son.”24 When Tseng moved to New York to join his sister in 1978 because he could not obtain a French resident visa, he did so as a queer man of color and artist policed by the über-conservative Reagan administration, and simultaneously as a transnational flâneur who was used to sponsored traveling and schooling as a way of living.25 For the East Meets West a.k.a. Expeditionary Self-Portrait Series, Tseng continued to travel across the world, posing for self-portraits of his Mao suit–clad alter ego in Canada, Brazil, Japan, etc.

Within this impressive, almost life-long itinerary, what is frequently unheeded is Tseng’s biographical dissociation from the communist figure that his performance and photographs conjure. In a historicist manner that references theater productions, news articles, and other components of the US mediascape, Metzger corresponds Chinese bourgeois subjects to qipao, a “traditional” body-hugging dress often rendered hyper-feminine in Anglophone imagination.26 Despite coming from a background that is highly evocative of qipao, Tseng goes for the garment that appears to be the opposite of it: the masculine, sexually oppressive, and communist Mao suit, according to its American codification.27 Taking into account this iconographic conflict between qipao and the Mao suit, one can argue that the determination of Tseng as having convincingly portrayed a traveling Chinese communist (and thus possessing any of that identity’s values)—based on the superficial coordination of his race and outfit—has neglected the historical complexity on the other side of the Pacific before and during the Cold War.

Addressing concerns that delving into Tseng’s Kuomintang and petite-bourgeoisie family/personal background might unfairly predetermine the interpretation his work, my argument aligns with Chambers-Letson’s nuanced understanding of performance and its documentation. As Chambers-Letson argues, despite his reservations against over-interpreting Tseng’s identity as an Asian subject, “Tseng has deployed queer sensibilities alongside his racial difference to achieve a formal and critical effect within his photographs.”28 To infer that Tseng’s performance is relatable to his personal and family life is along the line of interpreting Tseng’s performance based on his racial difference. After all, the artist’s ideological beliefs and racial identification are biographical factors to contemplate when investigating a body of performative-photographic work that chooses identity as its material and names itself “Self-Portraits.”

My argument focuses on the dissonance implicit in the relationship between Tseng and what his costume signifies. However, I do not argue to completely distance Tseng from being read as a communist. As mentioned previously, Tseng does ostensibly and momentarily appear as a communist cadre to many onlookers, and this appearance, when received, has its geopolitically critical connotations. It is the near-permanent alignment of the artist with the values that the outfit represents that is worth reexamining. In Asian American and performance studies scholar Vivian L. Huang’s book chapter, which pioneeringly focuses on the “distance” manifest in Tseng’s performance and photographs, Huang sharply identifies that “Tseng does not need to be a communist to be read as one.” This gesture towards recognizing Tseng’s work poses a critique of Cold War orthodoxies, where Chineseness is read automatically as communist and antithetical to democratic capitalism.29

Huang’s recognition of the communist reading of Tseng serves as a preamble to her thesis on Tseng’s apparent inscrutability and its sense of queer distance to the American imaginary, but the distance that this essay concentrates on evokes instead a transnational relationality. In her book chapter, Huang focuses on the inscrutable Chinese performed by Tseng and theorizes the figure as a ground for affective, disidentificatory distancing—which works against the antirelational definition of distance to embrace “a queer diasporic practice of relating.”30 Within this framework of distanced-relational practice, Tseng’s disaffected performance turns to enact a queer-of-color critique of the white, heteronormative milieus of American society. More importantly to Huang, as Tseng’s performance interfaces with American histories, with the aversion of the performance to positive figuration, it peculiarly registers the triangulated racial violence that has been invisiblized under “racial capitalism.”31 Huang’s theorization of the queer distance inspires this essay to direct its attention to the distance of ambivalence present in Tseng’s work. Ultimately, this essay aims to shift away from a discourse delimited by national borders, not merely for the fact that transnationality is an under-discussed aspect of Tseng’s work. To put it briefly, transnationality also defies the modern logic of always attempting to locate things within a given scheme of geographic, racial, and social configuration, and through this defiance, we can try to conceive knowledge not undergirded by existing hierarchical orders.32 It allows us to consider Tseng in less romanticizing manners that might overly identify him with US minoritarian identities.

Revisiting the originary East Meets West Manifesto can aid us in pondering this transnational distance of ambivalence. As I have demonstrated earlier, Tseng depicts and enters a diplomatic and ideological limbo that he as a conceptual artist in disguise seeks to transcend. However, if one were to let this photograph resonate within the context of Tseng’s personal life, the PRC national flag, employed here as the photographic backdrop, then merits focused attention. In front of the smooth PRC flag, which appears to carpet the studio floor by stretching all the way from the back, Tseng stands in a resolute manner that, paradoxically, also betrays an undercurrent of eager anticipation: the Mao suit has been crisply ironed with traveler’s creases on the pant legs, but within the dynamic pose, it takes on wrinkles that suggest motion. His stance, with one foot forward, conveys a preparedness to stride, while the shutter release cable is not taut but slightly coiling, hinting at a sense of bounce, movement, and hurry.

Differentiated from an archetypal socialist realist style that thoroughly romanticizes details to elevate quotidian scenes into idealized moments wanting to last indefinitely, Tseng’s use of the socialist Chinese ensemble almost betrays an “internal strife.” The smoothness of the PRC flag offers a subtle divergence from the Maoist figure trapped in a moment of haste. As he remains in physical contact with the US flag that was clearly in a rumple before being hung, Tseng comes to embody a mental distance situated between him and the unwrinkled national symbol left behind by him. To an extent, this mental distance “performs the proximal/distant affiliation” that Huang writes of the relationship between Tseng and the war history of Puerto Rico latent in one of Tseng’s photographs.33 By giving form to an ambivalent entanglement between Tseng and the communist iconography, East Meets West Manifesto unfolds, perhaps inadvertently, the life story of an artist who comes into the diaspora following the Chinese Civil War, a war fought partially at the dawn of the world-dividing Cold War.

Racialization and Its Shadows: SlutForArt as an Alternative Strategy

A short comparison between the reception of Tseng’s work and that of artist Nikki S. Lee’s (b. 1970) early work allows one to contemplate a potential reason behind the under-exploration of the transnational tensions underlying Tseng’s appropriation of the Mao suit. Having been compared with each other from time to time, Tseng and Lee both utilize masquerading techniques and stage identity performances in presumed public spaces.34 The differential reception of their work can be attributed, in part, to the complexities of representation and the question of its rightful ownership. Generally speaking, in US contexts today, differences in racial experience among a “Black” subject, an “American Indian” subject, and an “Asian” subject exist and are reified by authorities such as the Census Bureau as perceptually relatively stable.35 This act of reification necessarily essentializes the concept of race “as something fixed, concrete, and objective,” when racial meanings are messy, unstable, and vary across generations.36 Corresponding to the nationally stabilized differences, which could help keep power imbalances rooted in racial history somewhat in check while perpetuating certain established differences, a fine but firm line between transracial empathy and cultural appropriation is established.

An examination of Lee’s early art practice and its reception in the United States can shed light on how, sometimes, the insistence on broad-stroke racial and ethnic distinctions can overshadow other interpretive considerations, regardless of the artist’s intent. Lee’s lighter skin tone endows her privilege in terms of mainstream social acceptance in the US society, and it is associated with a racial heritage different from many of her temporary compatriots’. Yet, in her “Projects” series (1997–2001), where she changes her appearance to fit into various communities, Lee chooses to cross the racial line without much premeditation. This is evident from considering her appearance in some of the “Projects,” such as The Hispanic Project (1998; fig. 3), in conjunction with the fact that Lee intends to substitute fashion styles for cultural and racial identities.37 Therefore, to an American audience, her relatively insensitive adoption of Black and Latina identities through blackface and brownface, along with her capitalization of racially informed inequalities, appears problematic regardless of her own reasoning.38 It is in this condition that critic Eunsong Kim’s polemic against Lee’s practice of blackface and brownface is justified.39

In this milieu that emphasizes racial and ethnic distinctions, Tseng as a Chinese in diaspora self-portraying a Chinese identity is automatically deemed justifiable, even if the nuanced bond between Tseng and the adopted identity of the Maoist cadre requires certain unpacking. This highly racialized reading of Tseng’s performance is picked up by multiculturalist purveyors in the US art world during and after the 1980s and 1990s. In Dan Cameron’s short article “Alone Again, Naturally,” Tseng is understood as “visually focusing on his Chinese-ness.”40 This contrasts with the more transnationally minded understandings of Tseng as, first, focusing on the prevalent US perception of all Chinese as communists and, second, investigating the Cold War frictions between Chinese Kuomintang members and communists. Tseng’s East Meets West Series provides much more than the figure of the racial other for domestic contemplation, since his Maoist-appearing persona is transnationally meaningful beyond the US multicultural context.

As Tseng fashions his racial identity consistently in his work, Tseng’s familial struggle against communism during and after the Chinese Civil War as well as his personal ambivalence to communist values are underacknowledged behind Tseng’s communist façade. In a sense, the performed racial difference takes center stage in the ethical evaluation of identity performances. Its perceived dynamics, whether consistence or conflict, with the rhetorical identity of the artist create the fold where criticisms occur. Contrary to Tseng and his work, as soon as Lee ventures out of the “Asian” characters to which her biography seems to subscribe her, her work becomes susceptible to a critique based on fair representation as it tilts dangerously towards racially exploitative measures. The costume changes that Lee renders hyper-flexible and uses as key to her “immersive experiences” provide the basis for charges of insensitivity and racism.41 On the flip side of this controversy, when Lee makes Korean and Japanese American identities parts of her work (fig. 4), her work is seldom questioned for yellowface or investigated for its negotiation between Asian and Asian American identities.42 Instead, Lee is understood as “no longer about sticking out like a sore thumb” by some of her critics in those scenarios.43

The Schoolgirls Project (22), 2000

Chromogenic print

Artwork © Nikki S. Lee, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Choreography by Ping Chong and Muna Tseng

© Muna Tseng Dance Projects, New York. www.munatseng.org

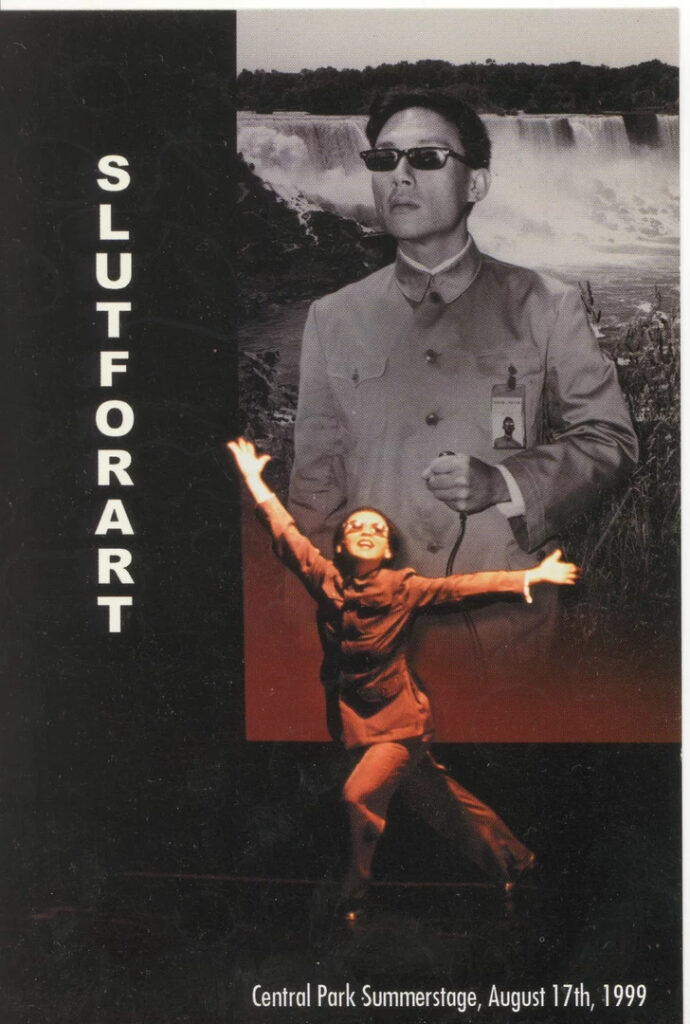

An alternative interpretative strategy, which also happens to be a work of performance art, can help us place racialization in relation to other aspects of Tseng’s work, such as those that are transnationally concerned or uninhibitedly queer bourgeois. Ping Chong and Tseng Kwong Chi’s sister Muna Tseng’s dance-theater piece SlutForArt (1999; fig. 5) provides an intimate and sorrowful understanding of Tseng Kwong Chi’s oeuvre that is also well-rounded in terms of its reading of Tseng’s cultural and political leanings. No longer fixated on the figure of the racial other that the Mao suit–clad Tseng might have symbolized, SlutForArt is interested in returning Tseng to his multifaceted life in Hong Kong, Canada, Paris, and New York, surrounded by like-minded and daring friends. This is indicative of the title SlutForArt, which implies a fearless attitude and camp endearment while referencing the moniker that Tseng gives himself on the badge. “Scene 7: Things-My-Frère-Liked Dance” exemplifies the attempt to illustrate this life of Tseng, which oscillates between the ascetic communist trope and the exuberance of consumerist lifestyles. In this scene, Muna Tseng enters the stage in a black Mao suit, with the slide projection behind her listing things that Tseng Kwong Chi enjoys: “Sole Picasso, Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita… Drunken crabs at Double Happiness, Rita Hayworth’s brows, Black truffle omelette, Marilyn Monroe…”44 The list goes on, referencing popular culture, food, film, music, and dance. Hedonist pleasures particular to Western Europe and North America fill the list, but the dandy details are deliberately absented by the black Mao suit. Before and after “Scene 7,” mentions of Tseng’s racial difference dot the script; so do those of Tseng’s musings on art and photography. Given that this is a commemorative artwork, certain posthumous edits are expected despite its confessed reliance on interviews with Tseng and his friends.45 Even so, the viewer can still get a taste of the myriad contradictions that make up Tseng’s life and art beyond his partial alignment with the queer-artist-of-color critique.

Conclusion

Taking a brief detour into the established discourse of Tseng in landscapes—and within multiple landscape traditions—offers an insightful parallel to the intricate dynamics at play in Tseng’s appropriation of the Mao suit. In “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Eugenic Landscape,” Asian American studies scholar Iyko Day considers the Mao suit–clad Asian body of Tseng in his Expeditionary Series an “alien excess” on North American landscapes. Tseng’s reference to early twentieth-century landscape traditions in Canada and the United States brings forth and cracks open the eugenic ideology that builds “race science, white nativism, and settler nationalism… into the landscape.”46 While Day’s article emphasizes the queer Asian sensibilities that Tseng has at hand, it also stresses Tseng’s acute perception of Western landscape traditions, crediting Tseng for his apt appropriation and adaptation of iconic images.47 The framework of disidentification is likewise important to Day’s interpretation, but Tseng’s disidentification is not so militant thanks to his guerilla-style Maoist masquerade; it is rather reliant on the directory of landscape motifs from which it borrows and with which it tacitly contends.48

If Tseng’s reference to landscape conventions in his Expeditionary Series has regenerated the symbolism associated with Canadian and US natural subjects, then in the performance where the Mao suit takes precedence, Tseng has enabled his audience to dwell on the many possible connotations of the outfit, along with their potential contradictions with one another. To gain access to and later critique the social environments that habitually exclude Tseng is undoubtedly a role performed by the suit. However, when the viewer considers the distance of ambivalence between Tseng the Chinese other and Tseng the conceptual artist manifested in artworks such as East Meets West Manifesto, one can look past the instrumentality of the suit and tap into the transnational complexity of the act of appropriating the outfit. This complexity is showcased most strongly in its negotiations with Cold War histories on both politically commentative and intimately personal fronts. In addition, the transnationally meaningful Mao suit can question the dominant role played by racial and ethnic distinctions in evaluations.

Constituting a reality that artists of color grapple with daily in North American societies, racial and ethnic differences are not to be sidelined in favor of a post-racial perspective. This is because boasting a postidentity discourse would mean to succumb to a neoliberal world order hinging on an illusional and often underexamined meritocracy, which is becoming all the more blatant today as the US Supreme Court overturns affirmative action. Nevertheless, given that Tseng Kwong Chi’s work conveys themes beyond the racial and sexual identities of his marked by multiculturalism, it is only fair to take up the distance between Tseng and his Maoist persona, perusing it to attend to the transnational and appropriative aspects of Tseng’s oeuvre.

Notes

1. Sean Metzger, “Part III: The Mao Suit,” in Chinese Looks: Fashion, Performance, Race (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2014), 164. For reasons to do with consistency with previous English-language scholarship as well as recognizability, the “Zhongshan suit” is hereafter referred to as the “Mao suit,” but it should be noted that Zhongshan is an equally accepted name of the attire, if not more so, and the outfit is almost exclusively known as Zhongshan in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) today, for instance.

2. Vollmer, John E., Verity Wilson, and Kate Lingley, “China: Textiles and Dress,” in Grove Art Online, October 10, 2023, accessed November 10, 2023, https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1093/oao/9781884446054.013.90000371738.

3. Metzger, “Part III,” 164–5.

4. The series is hereafter referred to as “the East Meets West series” or “the Expeditionary series,” depending on the specific works within the series being invoked for analysis.

5. By “infiltration,” I am referring to Joshua Chambers-Letson’s catalogue essay titled “On Infiltration,” which discusses some of Tseng’s works by analyzing their queer militant potential and tactics. Joshua Chambers-Letson, “On Infiltration,” in Tseng Kwong Chi: Performing for the Camera (Norfolk, VA: Chrysler Museum of Art, 2015), 87–118.

6. Warren Liu, “How Not to See (Or, How Not to Not See) the Photographs of Tseng Kwong Chi,” Amerasia Journal 40, no. 2 (2014): 27–8, https://doi.org/10.17953/amer.40.2.90v225666718561l.

7. Here, I use the term “disidentificatory” to refer to analyses that premise their findings on performance theorist José Esteban Muñoz’s theorization of “disidentification.” Such analyses can be seen, for instance, in Chamber-Letson, “On Infiltration,” 102; Iyko Day, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Eugenic Landscape,” American Quarterly 65, no. 1 (March 2013): 93, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41809549. In Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, Muñoz articulates “disidentification” as an artistic process and strategy of resistance that “works within and outside the dominant public sphere simultaneously.” José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 5.

8. Tseng Kwong Chi: East Meets West, directed by Christine Lombard (1984), https://vimeo.com/58113614.

9. Amy L. Brandt, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Politics of Performance,” in Tseng Kwong Chi: Performing for the Camera (Norfolk, VA: Chrysler Museum of Art, 2015), 32. Chambers-Letson, “On Infiltration,” 87.

10. Muna Tseng and Ping Chong, “SlutForArt,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 22, no. 1 (January 2000): 120, https://doi.org/10.2307/3245920. In the commemorative performance work SlutForArt (1999), a large textual portion of which is based on interviews with Tseng’s colleagues and friends, Muna Tseng and Ping Chong quote Bill T. Jones speaking about the “blankness” expected of Tseng Kwong Chi.

11. My use of “fictional” and “rhetorical” identities is indebted to Cherise Smith’s conception of the two personae in her book Enacting Others. In this book that approaches the changing discourse of the “politics of identity” through analyzing works of performance art, Smith considers the rhetorical personae performed by artists through interviews and writings to be distinct from the fictional personae assumed by the artists during their performances. Cherise Smith, “Introduction,” in Enacting Others: Politics of Identity in Eleanor Antin, Nikki S. Lee, Adrian Piper, and Anna Deavere Smith (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 22–3, https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1215/9780822393085.

12. It should be emphasized that I am not arguing that the “infiltration” model observed in Tseng’s work is non-existent or ineffective. As Chambers-Letson has demonstrated in “On Infiltration” and later in book chapter “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Party’s End,” for the Moral Majority Series (1981), for instance, Tseng makes strategic use of his costume (here a seersucker suit befitting an adopted conservative journalist identity) to exercise guerilla tactics and convince Daniel Fore, among other members of the Christian, right-wing political organization Moral Majority, to stand for portraits. My point is rather that there remains distance to be probed between the artist and his adopted costume. Chambers-Letson, “On Infiltration,” 109–12. Joshua Chambers-Letson, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Party’s End,” in After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 211–4, 10.18574/9781479882632.

13. John Philip Habib, “A Life in ‘Chinese Drag,’” Advocate: The National Gay and Lesbian Newsmagazine, April 2, 1984, 72, https://search-ebscohost-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=qth&AN=6394550&site=ehost-live.

14. Brandt, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Politics of Performance,” 38.

15. Tseng Kwong Chi, directed by Lombard (1984).

16. Tseng Kwong Chi, directed by Lombard (1984). Tseng made an error in the narration, mistakenly asserting that Richard Nixon went to China in 1979, which was instead the year he started his East Meets West Series. Nixon visited China in the official capacity of a US president in 1972.

17. Metzger, “Part III,” 167.

18. Metzger, “Part III,” 221.

19. Metzger, “Part III,” 193.

20. Brandt, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Politics of Performance,” 29.

21. Chambers-Letson, “On Infiltration,” 97.

22. Chambers-Letson, “On Infiltration,” 97.

23. Brandt, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Politics of Performance,” 26.

24. Muna Tseng, “A Tale of Two Siblings: Kwong Chi and Siu Chuk (a.k.a. Joseph and Muna) Tseng,” in Tseng Kwong Chi: Performing for the Camera (Norfolk, VA: Chrysler Museum of Art, 2015), 141–8.

25. Brandt, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Politics of Performance,” 29.

26. “This discourse attached to the Mao suit in Time and other venues diverged significantly from the association of the qipao in roughly the same era, when the sheath shaped women as agents and objects of capitalism… These different looks generally situated Chinese bodies in metonymic relationship to Hong Kong and China, which constituted different timescapes of capitalist and socialist modernization.” Metzger, “Part III,” 162–3. For the Anglophone cultural trope of a Chinese female character dressed in qipao and operating in a capitalist, bourgeois society, see the British stage play The World of Suzie Wong (1958) and the eponymous British-American film made in 1960, as well as Hollywood actor Anna May Wong cast in qipao and sheath-shaped outfits inspired by qipao.

27. Since the Mao suit worn by Tseng tends to be more iconically donned by male persons than female persons, qipao here can be expanded to include its male counterparts, such as the traditional changshan or the tailored Kuomintang military outfit, worn by the Kuomintang leader of China, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, in the company of the qipao-clad Madame Chiang/Soong Mei-ling. Additionally, it is worth noting that Chiang Kai-shek frequently donned the Zhongshan suit (here, slightly different from the later Mao suit) for photographs and public occasions, given the seminal role of Sun Zhongshan/Sun Yat-sen within the Kuomintang party and founding history of the Republic of China (ROC). In this passage, it is only within the late–Cold War US context—the context with which Tseng’s work interacts most immediately—that the Mao suit is contrasted with qipao. Ibid., 161–8.

28. Chambers-Letson, “On Infiltration,” 99.

29. Vivian L. Huang, “Distance, Negativity, and Slutty Sociality in Tseng Kwong Chi’s Performance Photographs,” in Surface Relations: Queer Forms of Asian American Inscrutability (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 144, https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1215/9781478023623.

30. Huang, “Distance, Negativity, and Slutty Sociality in Tseng Kwong Chi’s Performance Photographs,” 137.

31. By “triangulated,” I refer to both the racial triangulation of Asian Americans, Black Americans, and white Americans and that of Indigenous, settler, and alien positions, both of which Huang discusses in relation to the Asian American racial position, its relationality, and queer distance. Ibid., 153, 162. The concept of the racial triangulation of Asian Americans is first raised by Claire Jean Kim and has been later taken up or similarly theorized by many other Asian Americanists. Claire Jean Kim, “The Racial Triangulation of Asian Americans,” Politics & Society 27, no. 1 (March 1999): 105–38, https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1177/0032329299027001005.

32. Naoki Sakai, “The Regime of Separation and the Performativity of Area,” positions 27, no. 1 (February 2019): 241–279, https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1215/10679847-7251910.

33. See Tank, Puerto Rico (1987) by Tseng Kwong Chi. Huang, “Distance, Negativity, and Slutty Sociality,” 160.

34. For examples of existing comparisons between Tseng and Lee, see Brandt, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Politics of Performance,” 62–71; Irene V. Small, “Spectacle of Invisibility: The Photography of Tseng Kwong Chi and Nikki S. Lee,” Dialogue (Spring–Summer 2000).

35. For the mentioned categories named differentially as “White,” “Black or African American,” “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Asian,” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander,” see “About the Topic of Race,” United States Census Bureau, March 1, 2022, https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html.

36. Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s (New York and London: Routledge, 1994), 54.

37. William L. Hamilton, “Shopping with Nikki S. Lee: Dressing the Part Is Her Art,” New York Times, December 2, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/02/style/shopping-with-nikki-s-lee-dressing-the-part-is-her-art.html.

38. There is contention regarding whether Lee participates in, for instance, the blackface tradition, and this essay acknowledges the ambiguity. This is because Lee’s appearance with a darkened skin tone among Black Americans can gesture towards an American urban phenomenon where Asian Americans become acculturated to Black American fashions and tastes. See Smith, “Nikki S. Lee’s Projects and the Repackaging of the Politics of Identity,” in Enacting Others, 219.

39. Eunsong Kim, “Nikki S. Lee’s ‘Projects’—And the Ongoing Circulation of Blackface, Brownface in ‘Art’,” Contempt+orary (blog), May 30, 2016, http://contemptorary.org/nikki-s-lees-projects-and-the-ongoing-circulation-of-blackface-brownface-in-art/.

40. Dan Cameron, “Alone Again, Naturally,” in Tseng Kwong Chi: Ambiguous Ambassador (Tucson: Nazraeli Press, 2005), 3.

41. By “immersive experiences,” I refer to the “weeks or months each project takes,” as Lee goes into communities to form temporary relationships with people and produce snapshots of her taken by others. The immersion is visually conveniently reflected by Lee’s apparent acculturation, which is facilitated by her sartorial and style choices. Hamilton, “Shopping with Nikki S. Lee.”

42. See The Schoolgirls Project (2000) and The Young Japanese (East Village) Project (1997) by Nikki S. Lee. One account that analyzes Lee’s participation in yellowface is Smith’s, as Smith heeds the artist’s self-transformation from a Korean immigrant to an urban Asian American person occupying a differentially othered position. Smith, “Nikki S. Lee’s Projects,” 219.

43. Gilbert Vicario and Nikki S. Lee, “Conversation with Nikki S. Lee,” in Projects (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2001), 104. See also Guy Trebay, “Shadow Play,” New York Times, September 19, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/19/magazine/shadow-play.html for a brief comment on Lee’s “immutable… physiognomy and race,” which forms the premise for the imperception or hyper-perception of Lee’s identity transformations.

44. Tseng and Chong, “SlutForArt,” 121.

45. Tseng and Chong, “SlutForArt,” 111.

46. Day, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Eugenic Landscape,” 115.

47. Day, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Eugenic Landscape,” 91–118.

48. Day, “Tseng Kwong Chi and the Eugenic Landscape,” 93–4, 98, 115–6.