Introduction

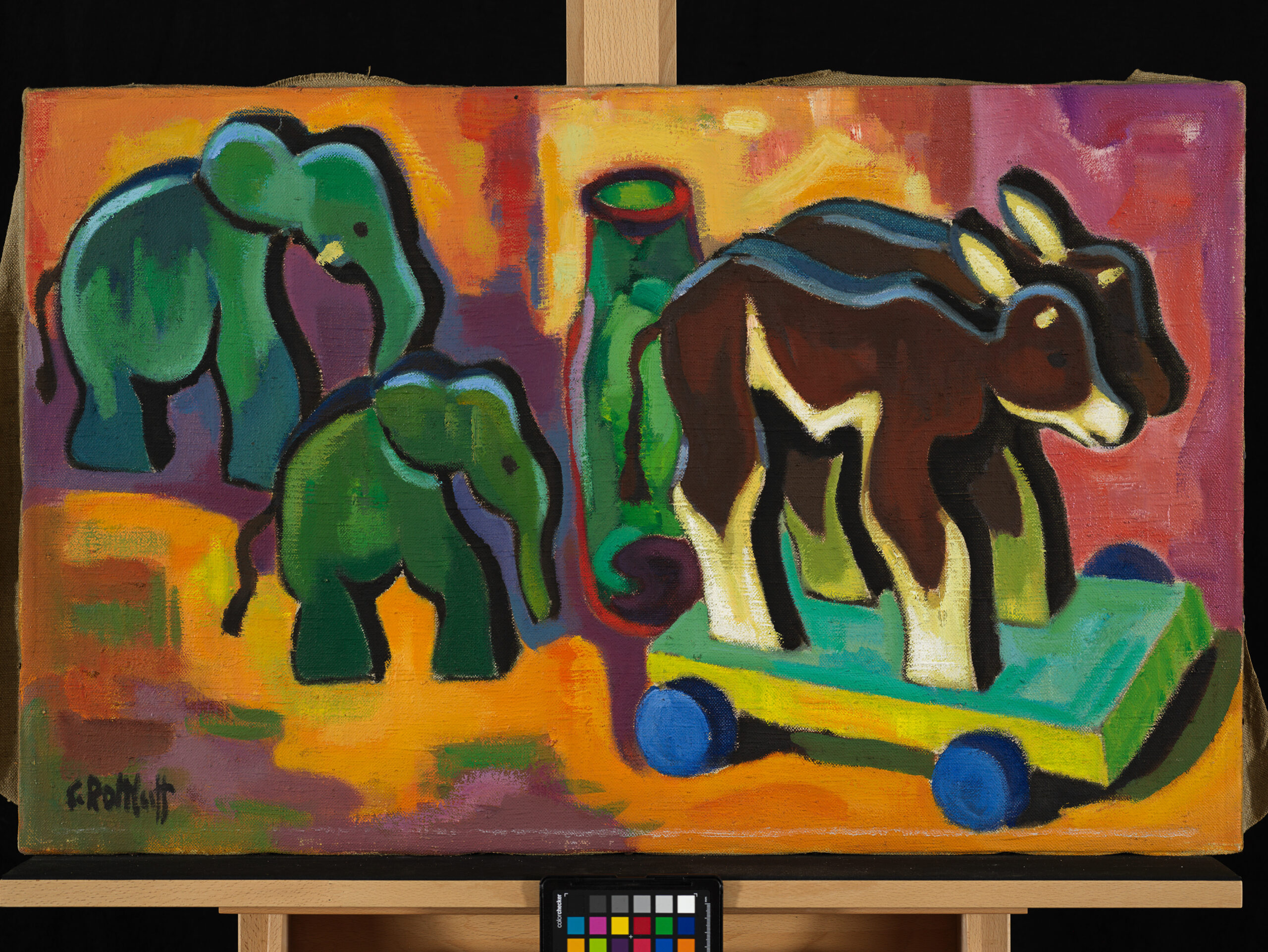

The painting Spielzeug (Toys) depicts two toy elephants and two toy calves ordered head-to-toe in a line (Fig. 1). A meandering stream of orange below the animals endows the static picture with a sense of motion. If the figurines were to become animate, a much longer procession would pass across the picture’s tightly cropped frame. With brush and oil paint, the elderly artist returned to a popular childhood pastime: Noah’s Ark. In this imaginative game of make-believe, a pair of all species on earth line up to board a cavernous ship, where they will be protected from the impending great deluge.

The German expressionist Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884-1974) painted Spielzeug in 1947, just two years after World War II (WWII). In the same year, Schmidt-Rottluff produced fifteen other oil paintings, a medium barely practiced since the 1930s. The painter’s yearning for childhood, a period of life experienced by the artist during the German colonial empire (1884-1914), coincided with the end of his wartime artistic hiatus and renewed creative tenacity. The central question of this essay is what politics, morality, and understandings of the subject, specifically, of boyhood and manhood, are recuperated for this pivotal historical moment by the artist’s nostalgia for innocence and play?

Schmidt-Rottluff’s postwar paintings have received scant art historical attention compared to artwork from his youth when the artist group Die Brücke (1905-1913) was still active, the movement for which Schmidt-Rottluff is known. Rather than sideline works from his late oeuvre as superfluous iterations of old artistic formulas, this essay argues that his works from the immediate postwar period regenerated anachronistic colonial values. Through comparison with his contemporaries, I will show how Schmidt-Rottluff’s personal rediscovery participated in a larger resurgence of colonial ambitions in postwar German society. By examining German colonialism within an expanded temporality, this paper implicitly rallies against two common mistaken assumptions: that the historical significance of German colonialism and the German colonial imaginary are restricted to the period before World War I (pre-1914) and their impact is less severe than those of the British and French empires.1

Schmidt-Rottluff’s fame dates to his student years at the Dresden University of Technology (1905-7), where he studied with Erich Haeckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Fritz Bleyl, other founders of Die Brücke. Inspired by the boisterous spirit of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), especially his philosophical novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883), the four students channeled the revolutionary energy of youth, seeking spiritual rejuvenation and rejecting what they saw as a moral contemptuous and stultified society. They also sought to break free of tedious academic conventions and schooling. Traditionally, Die Brücke is known for intense colors, the distortion and exaggeration of figures, and experimentation across mediums. Many of the artists also pursued the complete integration of art and life, transforming their living quarters into loud bohemian interiors. The movement is remembered today, alongside Der Blaue Reiter, as one of the main progenitors of German Expressionism.2

However, this so-called renewal relied on primitivism, a reactionary impulse towards people subject to colonial rule outside of Europe.3 Primitivism denied the coevalness of indigenous society, projecting its material culture into the past, while simultaneously romanticizing it as uninhibited, expressive, and formally innovative. In 2021-2, following many decades of academic reckoning with the movement’s unsettling ambivalence, the Brücke-Museum in Berlin assembled the exhibition Whose Expression? The Brücke Artists and Colonialism in 2021-2 to further interrogate questions of cultural appropriation and the movement’s entanglement in the colonial apparatus of power.4 This important exhibition participated in recent efforts to decolonize Germany’s ethnographic museums, which has involved the restitution of the Benin Bronzes, the repatriation of human remains, and significant institutional rebranding. The show investigated how Die Brücke artists directly and indirectly benefited from the German empire. It recounted visits of the artists to ethnographic museums, so-called “human zoos,” and their travels to German colonies. The exhibition pointed out explicit instances of formal appropriation from looted objects, while also critiquing those of dehumanization and eroticization. Although not immediately obvious in the exhibition itself, this critique has been mounted by a long cast of critical dissenters. The Marxist critic György Lukács (1885-1971), for instance, took issue with the movement in the 1930s.5 In 1968, the German-born art historian L. D. Ettlinger (1913-1989) further researched the specific visits of Die Brücke artists to ethnographic museums, unpacking links between primitivism and Nazi race ideology.6 In the 1990s, modernist art historian Jill Lloyd (1955-) elaborated this research by tracing Die Brücke artworks to specific objects from various parts of the colonial empire.7 Die Brücke has counted – perhaps since the movement’s inception – as one of modernism’s most questionable chapters.

These previous studies all critiqued the complicity of Die Brücke with German colonialism during the lifetime of both entities, focusing on history predating World War I. Extending these trans-generational critiques of Die Brücke, this essay focuses on Schmidt-Rottluff’s late oeuvre, which presents the opportunity to understand how postwar German society juggled two horrifying legacies, colonialism and Nazism. I argue that Schmidt-Rottluff’s paintings and the household objects depicted within them became the resting ground for latent colonial ideology, which became reactivated in German international environmental policy of the 1960s.

In the first section, I contrast Spielzeug with fragments from Minima Moralia: Reflections from a Damaged Life (1951), an unrelenting, pulverized account of the end of European morality by the German critical theorist Theodor W. Adorno (1903-1969). The comparison shows how the destruction wrought by WWII gave rise to widely divergent opinions about rejuvenation, colonialism, and collecting. In contrast, section two discusses the similarity between Schmidt-Rottluff and a different contemporary, Bernhard Grzimek (1909-1987), the longtime director of the Frankfurt Zoo. Grzimek’s experience of rebuilding the bombed-out facility heralded his conservation work in Africa decades later. Moving from the collection of living animals to objects, section three contextualizes Schmidt-Rottluff’s habit of lining up his collections within a genealogy of such practices at ethnographic museums dating to the German colonial era. The fourth section of this essay analyzes the immediate postwar reception of Schmidt-Rottluff. Critics habitually returned to the artist’s strength and imposing physical presence, despite his art being conspicuously small and intimate. After the war, there was a need to salvage a piece of German cultural heritage, one that wasn’t complicit with National Socialism, but also not completely humiliated and emasculated by defeat. Schmidt-Rottluff’s considerable size made him a convenient target for attributions of endurance and integrity, the alleged qualities needed to rebound from the depletion of the past.

I. Two Different Views of Catastrophe: Minima Moralia and Spielzeug

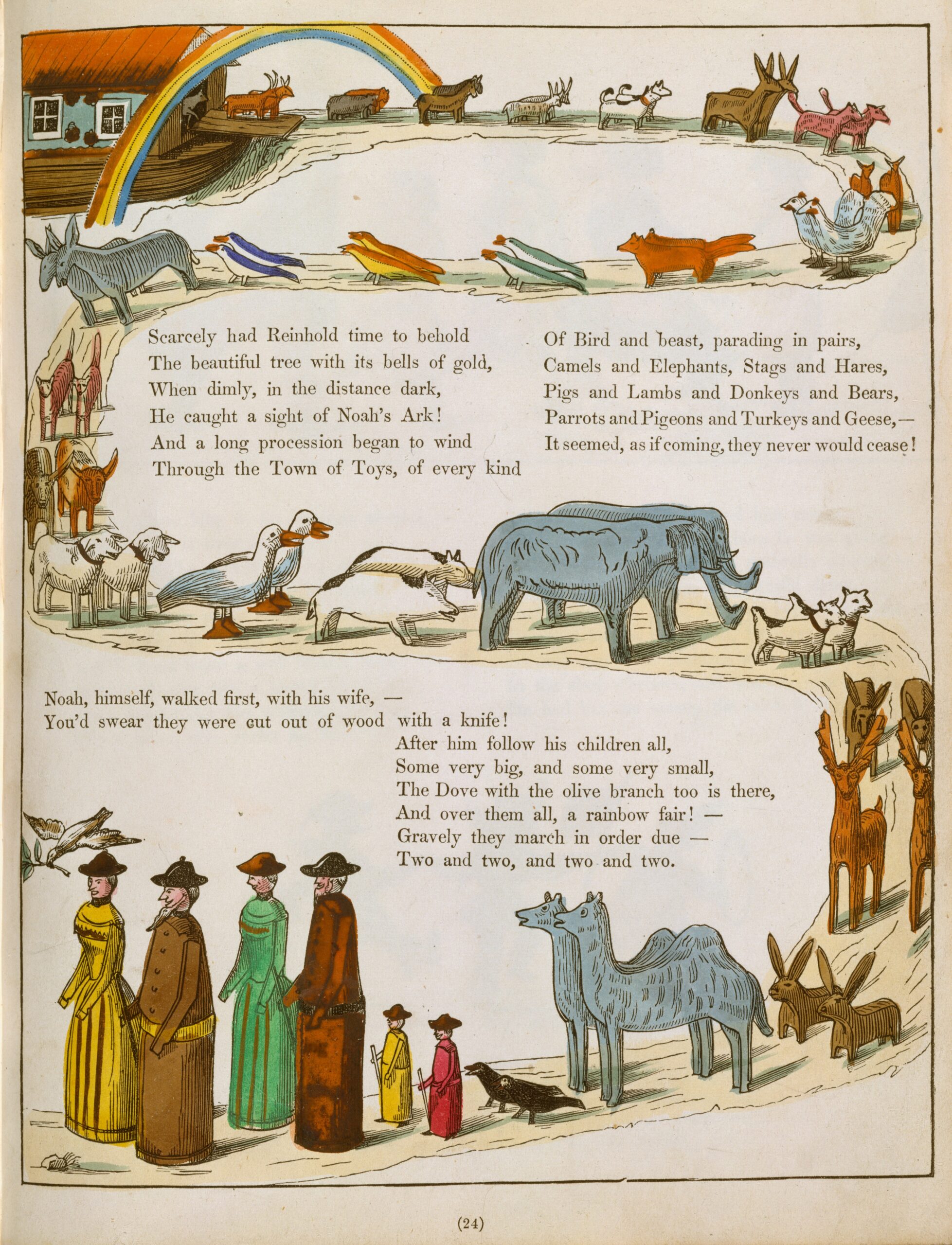

Chemnitz, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s birthplace, is a medium-sized town in Saxony located along one of the main trading axes for wooden toys, ornaments, and decorations produced in the region’s Iron Mountains. Until the Great Depression, Noah’s Ark sets were among the most popular and widely exported goods (Fig. 2).8 Although toy historians agree the popularity of Noah’s Ark toy sets peaked in the 19th century, they were still widely available in Germany after 1945. Many of these sets were produced in a cluster of small mountain villages, just southeast of Chemnitz, before traveling to Nuremberg for international distribution. Unlike so many other African masks or ritual objects in Schmidt-Rottluff’s paintings, the specific toys depicted do not belong to the Karl and Emy Schmidt-Rottluff Foundation today. Perhaps they were omitted from the collection precisely because they seem unexotic and ordinary.9

Before painting Spielzeug in 1947, Schmidtt-Rottluff lived between 1943 and 1946 in his childhood home, a respite from constant aerial bombardment in the city. Back in the province, Schmidt-Rottluff gained renewed intimacy with his past, encountering former habits, feelings, and memories. Instead of devoting his time to teaching and making art, he tended the garden just like his father before him who was a miller. After the war’s end, he eventually returned to the city, obtaining a professorship in 1946 at the Hochschule für Bildende Kunst in Berlin. Nonetheless, Schmidt-Rottluff called on objects retaining the aura of his childhood and the cottage industry of the mountains to reinvigorate his career. The age-old biblical story of Noah, proffering a new beginning after catastrophe, became an allegory repairing his artistic practice and the larger restoration of German society.

While some may be sympathetic to this hopeful message, I caution that use of the biblical story at this juncture reactivated ideologies of German colonialism. Other people who witnessed the war’s horrors, renounced regeneration once and for all. Theodor W. Adorno’s fragment “Mammoth” from Minima Moralia contains a sharply contrasting, staggeringly pessimistic argument about Noah’s Ark.10 For Adorno, humanity was blind to own wrongdoings and evils, but nonetheless had a deeply troubled conscious, seeking redemption on a subconscious level. Modern sensations and fantastical characters served the crucial function of reconciliation. Adorno points to the examples of King Kong, who takes revenge on a metropolis, or the discovery of a new Woolly Mammoth fossil that vastly upsets the previous date of the specie’s extinction, as evidence of a widespread desire for nature to survive the negative effects of civilization, such as environmental destruction, the systematization of death, and the totalitarian state. These modern sensations, just like the zoo, go back, according to Adorno, to the Judeo-Christian story of Noah’s Ark, which promises that after the earth is washed of sin, the next generation will be able to live with all the same animals, even more peacefully than before.

Referring to animals on the Ark, as well as those captive in zoos, Adorno writes, “[t]hey are allegories that the specimen or the pair defy the disaster that befalls the species qua species.”11 The peculiar wording of this sentence echoes an ambiguity in Spielzeug, which might otherwise clash with the common understandings of Noah’s Ark. In contrast to the elephants, who clearly resolve into two distinct animals and are even gendered male and female by the respective presence and absence of tusks, the two nearly identical calf bodies might be the left and right profiles of a single animal.12 Despite how a heteronormative world view may lead to the belief that binary gendered pairs from every species boarded the ship, there is little scholarly consensus about the actual number of animals specified in the Torah.13 Adorno’s ease in sliding from “the specimen” to “the pair” shows that the story’s function is not dependent on the exact number of animals. Rather, the story’s lesson introduces the miraculous possibilities of metonymic substitution, a fundamental logic of thinking and communication.14 The few creatures selected for Noah’s Ark ensure the survival of a whole species, typically comprised of innumerable individuals. Playing with the toy animals, which entails preconceptual thought processes of scaling something unfathomably large down to something small and manipulable, as well as rescaling it to something large again, develops the child’s use of metonymy. For Schmidt-Rottluff, the process entailed regenerating his adult life and artistic practice from isolated fragments of childhood.

Both Minima Moralia and Spielzeug were made between 1944 and 1947. Each is a stance on the possibility or impossibility of upholding old values in the postwar era.15 Similar to how aerial bombing reduced countless buildings to rubble, both works operate in piecemeal. While Minima Moralia is composed of 153 self-sufficient thoughts without the sinews of a larger argument, Schmidt-Rottluff focuses on a fragment of a much longer procession. When compared with toys, Adorno’s aphorisms possibly begin to look like cute quips for children, rather than weighty ruminations. Adorno’s resolute negativity, though, throws Schmidt-Rottluff’s peculiar optimism into sharp relief. In the next section, I will discuss at length the moment when Schmidt-Rottluff found artwork and collections in his old cellar, all of which he thought had perished in the war. The survival of these objects raised the possibility of amassing new ‘exotic’ things from distant places.16 Adorno, by contrast, believed that collecting and preservation after the war would only assure the bankruptcy of European morality:

Only in the irrationality of civilization itself, in the nooks and crannies of the cities, to which the walls, towers and bastions of the zoos wedged among them are merely an addition, can nature be conserved. The rationality of culture, in opening its doors to nature, thereby completely absorbs it, and eliminates with difference the principle of culture, the possibility of reconciliation.17

Adorno pushes the reader towards the wild, uncontrolled forces abounding within the very structures (including physical ones, like border walls or cages, and abstract ones, such as laws and moral lessons) designed to enclose the supposed fragments of imported nature and culture. To continue extracting and collecting the nature ‘out there,’ that is beyond society, forestalls reckoning with society’s own breakdown inherent to the Second World War. Instead, Adorno urges reflection on the forces of containment and the violence splintering the task. His negativity pushes one to consider the unrealized potential of rebuilding European society after WWII without the structures of domination that simultaneously project nature beyond civilization and sequester the former within the latter’s bounds. Schmidt-Rottluff neither shares Adorno’s despair nor his radical vision of a future without containment. Rather, fragments are supposed to remultiply Schmidt-Rottluff’s old collection, like a pair of animals, the species after the flood.

II. War Rubble, Imperial Ruins, and Colonial Returns

In 1943, Karl and Emy Schmidt-Rottluff’s apartment in Berlin was flattened by an allied bombing raid. They fled to Chemnitz, where they found relative calm, before Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s family home was plundered by the Red Army in 1945. When they returned to Berlin in 1946, they believed their former belongings stored in the basement had perished or were stolen in the intervening period.18 Given the circumstances, it must have been a great relief to find everything beneath the rubble. Karl writes to his brother Kurt about the unbelievable discovery:

Rugs, blankets and painting canvases, strangely all there—Marie defended the basement like a lioness. Several kitchen dishes that M. saved have turned up— even the vacuum cleaner—only the cable burned…The watercolors were also there, even though some have mold on them, which can however be removed. Paintings are also partly moldy…3 wooden sculptures survived and were not burned for heating and some exotic things. One Samoan shell unfortunately broke—I will send it to you, maybe you can try to glue it, if you have time—it is an old piece.19

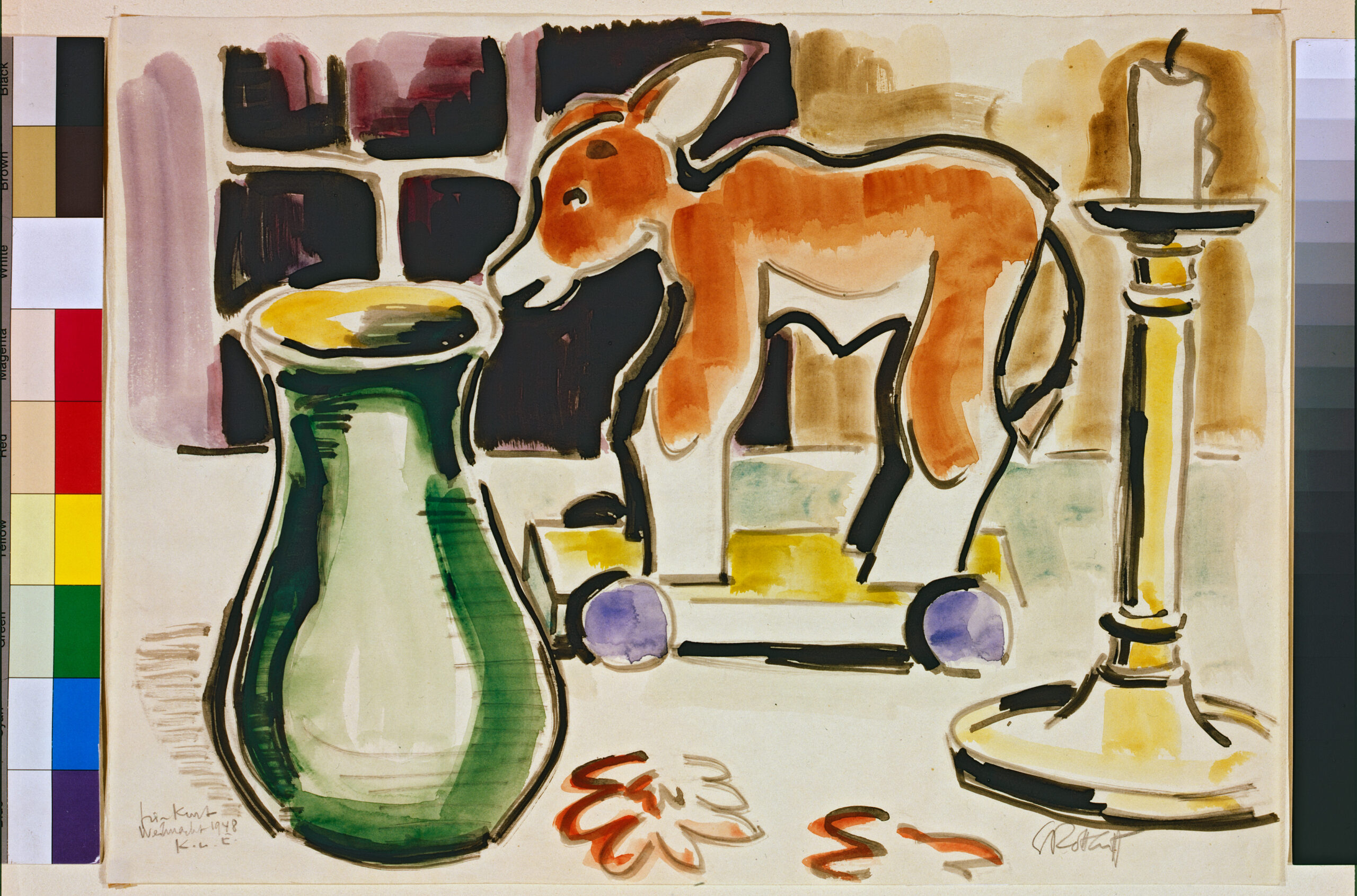

Even though still vulnerable to mold damage, collectibles were protected underground from the greater catastrophe unfolding above the surface, just like goods in the damp hull of a ship. The vacuum cleaner and Samoan shell—a difficult item to preserve whole—are arresting details of a domestic setting recently lost. Tropical objects in the Wunderkammer were supposed to sparkle, dust-free. In the same letter, we learn that a stray shard from this primordial atmosphere had become the chassis for the calf in Spielzeug. “[T]he rock slab is Solnhofer [a type of limestone from the eponymous town in Bavaria]—and picked up here out of the rubble—I used it as a base for the Kälbchen [small calf]—it stands very nicely on it.”20 Beginning with this act of mending, we can recount Schmidt-Rottluff’s engagement with the calf: first he picked up the lamed animal and positioned it upright on a shard of some lost tile.21 Later, he wrote to his brother to tell the tale, and shortly thereafter, he made an oil painting of the calf. Finally, in December 1948 he painted the calf again as a watercolor Christmas card for Kurt (Fig. 3).

The sculptures that were not burned are the well-known works Blauroter Kopf, Grünroter Kopf, and Trauernder.22 While Schmidt-Rottluff carved the wooden faces himself, he based their form on masks and objects from the East Zaire and the Belgian Congo.23 The shells are from Micronesia, where the German colonial empire ruled several islands. Observing that the presence of these objects in WWII rubble depended on colonial extraction and imperial trade networks earlier in the century suddenly changes the tenor of Schmidt-Rottluff’s rediscovery. Like countless collecting expeditions in the 19th century, the scene is charged with the excitement of obtaining riches and encountering the other. Considering this, Schmidt-Rottluff’s simile for Marie’s fierceness, how she “defended the basement like a lioness,” becomes more conspicuous. The elephant toys in Spielzeug are not just innocent childhood symbols, they must be seen as widespread signifiers of the colonial empire. Their seeming normality and everydayness, how the toys become a German pastime, results from the widespread diffusion of the colonial imagination and fantasies of the exotic.

Some readers might object that attention on such small objects sidelines more urgent concerns of postwar reconstruction. However, the toys are an opportunity to test hypotheses of historical continuity, whereas routine attention on the destruction and rubble (a focus of popular media and cinema: Germany, Year Zero [1948]) stresses a narrative of rupture and new beginnings.24 Against the narrative of the so-called ‘Stunde Null,’ (hour zero), historians now recognize that postwar culture anchored on the Weimar era. In terms of artistic authority, Meike Hoffman writes, “from May 1945, no break, no new beginning, no ‘Stunde Null,’ rather continuity since, at the latest the 1920s.”25 Schmidt-Rottluff and Max Pechstein’s postwar professorships in Berlin belonged to the initiative to rehabilitate the reputation of older artistic movements. Did re-institutionalization also rekindle primitivist fantasies?26

My focus on the toys, rather than the destroyed urban fabric, follows from Ann Laura Stoler’s discussion of “imperial ruins,” which are racialized representations and ongoing forms of subjugation that persist in zones of former colonial rulership.27 She defines the concept in explicit contrast to W. G. Sebald’s nightmarish descriptions of German cities at the end of WWII.28 “Here we are not talking about an event of bombardment and the fast-acting decomposition that follows. The ruins of the empire may have none of the immediacy of a freeze frame.”29 To consider the imperial ruin amidst the smoldering rubble of the war is an attempt to locate the continuity of colonialist ideology in the very instant in which it was supposedly severed.30 While it may be true that Germany’s division and occupation after the war meant that immediate postwar politics focused more on local affairs, the exaggeration of destruction, rupture, and victimhood produces a false sense of severance in the larger historical picture, between the German colonial empire and postwar West Germany of the 1950s and 1960s. The break enabled postwar political actors to posture as “neutral defenders” of nature in debates about habitat conservation in former African colonies.31

To better understand the politics of postwar conservation, it is instructive to revisit the dynamics between nature and colonial society at the turn of the 20th century. In German East Africa, the imposition of hunting permits and a new system of ivory taxes became pretexts to strip local populations of landholding rights and disrupt long-standing networks of political authority.32 As the ivory trade dwindled during the first decade of the twentieth century, vociferous debates about whether German East Africa was “a colony or a zoo” divided the white ruling class into opposing factions: settlers wanted to extinguish wild animals to make space for crops and livestock, whereas foreign nationals (of largely noble descent) demanded land conservation for scientific study and safari hunting.33 In this context, the animals in Spielzeug cannot simply be considered amicable companions, belonging together on the ark. German colonialists would have seen their relationship as one of mutual threat.

Cows were seen by conservationists to disturb so-called natural habitats, while elephants were feared by farmers because they spread sickness to livestock and trampled crops.34 The end of German colonial rule in Africa put a preliminary end to this conflict between wild and domestic animals, dubious categories in themselves. It was reanimated, though, in the late 1950s when controversy arose over the enlargement of Serengeti National Park. The part of Serengeti already under ecological protection had been sequestered by the German colonial government before WWI. In the postwar era, German conservationists lobbied to expand the park’s border to encompass the entire trajectory of the great migration of zebras, wildebeests, and gazelles. This led to further limitations of pasturelands for the Masai, which had been curtailed half a century before.

When Bernhard Grzimek, the main German proponent of conservation in the Serengeti, set off to Tanganyika to save the animals from the encroachments of civilization, he reinstalled the same opposition between nature and culture that had been brought there by the German colonial elite generations before him (Fig. 4).35 Grzimek’s confidence to determine what was best for Africa—an anachronistic assumption of colonial power—came from his success in regenerating the Frankfurt Zoo’s animal collection immediately after the war:36

The gradual recovery of animal populations in Frankfurt and other zoological gardens symbolized not just municipal reconstruction, but also the possibilities for redemption after the destruction of so much human life in a senseless war. Grzimek’s faith in nature’s unique regenerative capacity, which was forged in these troubled postwar years and then globalized as he began collecting expeditions to Africa would soon lead the zookeeper to fashion himself as a second Noah, leading the animals to safety among the rising tide of humanity.37

While the toys in Spielzeug do not explicitly represent the wild and domestic animals in Tanganyika, Bernhard Grzimek’s journey from the Frankfurt Zoo to the Serengeti parallels the growth of Schmidt-Rottluff’s collection in the postwar era. Initially starting with just a few exotic objects in the rubble, like the odd surviving monkey or snake in Berlin’s Zoo, the collection grew rapidly to a considerable size, housed today at the Brücke-Museum.38

This section raises the questions: what did objects with inconspicuous colonial heritages, like toy elephants or seashells, smuggle into the home at a time when Germany was supposedly no longer a major colonial power?39 What perceptions do these objects help cultivate of nature in faraway places? Reflecting on primitivism as a widespread cultural practice in the 1920s, the German art historian Charlotte Klonk observes that European collectors and artists brought non-European objects and animals into the home as sources of “spiritual and emotional…renewal” within their private lives.40 In addition to spiritual renewal, I argue that inconspicuous exotic objects disseminated a view of nature as something external from culture and society, but also, crucially, manageable from a distance. This is a colonial relationship to ecology exceeding the timeframe of historical colonialism. The elephants and calves in Spielzeug are not simply toys, but vestiges of imperial ruins. They stored earlier colonial outlooks on nature, making them available for redeployment in global environmental politics of postwar Germany.

III. Collecting, Organizing, and Researching at the Ethnographic Museum

For Schmidt-Rottluff, tidying-up was a means of mourning, processing, and moving on. In this section, I turn away from disorder resulting from warfare to investigate how clutter was a deliberate relation of force imposed upon natural and cultural objects stolen from the colonies. Until the curatorial strategy of Berlin’s Royal Museum for Ethnology was changed in 1926, the collection was presented in teeming masses irrespective of individual objects. More than learning about the use value or artistic merits of any given thing, visitors to the museum were baffled by an overwhelming sense of copiousness.41 In Berliner Museumskrieg, a polemic case made in favor of the museum’s reorganization, Karl Scheffler describes the dizzying atmosphere:

It could not be less overseeable, more like a stockroom and stuffier in the largest toy warehouses, in the most colorful antique shops, in the tightly filled vitrines of food stuffs. Enormous riches, things worth millions, expensive rarities are lined up next to and behind, over and under one another such that one almost begins to hate them. One cannot see any single object, the ruling throng is so extreme that only experts do not lose composure. Many objects are in hundreds there…according to a plan, but actually thrown carelessly amongst each other, one sees instruments of sacrifice, maps, casts from reliefs (up to a hundred meters long), dolls, musical instruments, Fayence ware and tiles, picture books, children’s toys…42

The list extends quite a bit farther, but this second mention of toys makes the similarities with Schmidt-Rottluff’s bombed-out cellar vivid enough. Colonial objects and European crafts sloshed around in the belly of the Völkerkunde Museum, as if being tossed by surges of the great flood. However, neglect or insufficient space for storage were not responsible for the disorder.43 Chaos was the primary step in the scientific method dominant at the time, the komparitv-genetischen Methode, in which objects of all different kinds, shapes, and uses, arriving from many different geographic regions of the world, were scrambled together to reveal novel similarities. These observations would then form the basis of longer inquiries. Since scholars have been unable to find a methodical, step-by-step account of the technique by its creator Adolf Bastian, historian of ethnography Sigrid Westphal-Hellbusch turns to Albert Voß, the first director of the Ethnographic Museum’s prehistoric department, for a sketch of the process:44

The appearances to be researched will be lined up amongst similar ones next to those that show the most relatedness. Won in this way, the lines of related appearances will then be grouped according to the degree of their relatedness and then compared again, in order to see if, and to what extent, they shared a place of origin, which influences were responsible for their differences and if one row possibly developed out of another…The more often these observations are made and the more all-encompassing and extensive the material for comparison becomes, the more conclusions it is that can be drawn out of the material. And the more frequent the same observations become, the safer it is to assume that they are correct.45

The komparativ-genetischen Methode, along with the complimentary curatorial strategy, has long lost popularity. After the Museum War, ethnographic museums around the world began to succinctly place singular objects in larger compositions of historical, geographic, and cultural unity. Individual works were then regarded for their unique qualities, no longer meant to stand-in metonymically as “mere evidence” of a much larger class of similar objects.46 Nonetheless, mixing widely variant things together, observing their similarities and lining them up, shuffling the results, only to line them up again, is a cultural habit that remains deeply ingrained beyond the museum. Children at play often sort and line up animal toys. As any child caretaker knows well, chaos erupts spontaneously throughout the game. With this oscillation between order and disorder in mind, we can think of the komparativ-genetischen Methode as the grown-up counterpart to child’s play. Schmidt-Rottluff participated in this long tradition of ordering chaos when he painted the calves, a green vase and two elephants in tow, and again, when he rotated the calves 180º and painted them again in the watercolor. This mode of tactile modeling is signature of his postwar oeuvre, where he repeatedly painted the same objects in different orders and new combinations.

While the creation of disorder was an intentional step of the komparativ-genetischen Methode, one should not assume that the process was overseen by collected and detached judgment. Regardless of whether objects were stolen, purchased, or received under questionable gift-giving circumstances, acquisition had to be rapid, according to the Völkerkunde Museum’s founder, Adolf Bastian. For him, rapid collection kept up with the ever-accelerating destruction of cultural heritage:47

A time, like ours, in which countless roots are destroyed with crude hands and the surface of the earth flows in all directions, owes it to the next generation, to save as much as possible from that which is leftover from the period of humanity’s childhood and youth for the understanding of the development of humanity’s spirit.48

Here, the founding principle of the ethnographic collection approaches the motive for building the Ark, only the apocalypse being prepared for was already unfolding. The fervent pace of collecting was not only driven by unbounded curiosity and the progress of scientific knowledge, it was also accelerated by panic about the loss of childhood. Brücke artists who visited the ethnographic museums throughout Germany were fascinated by the collected objects and recreated their forms in their own artistic work. In addition to pointing out that this was a form of appropriation, I argue that Brücke fulfilled a resuscitative role: it was a way of reinvesting the youth, supposedly stored in ethnographic museums, into aged, habituated, and stifling modes of social relatedness.

In addition to the primitivism directed towards indigenous societies living outside Europe, a second type of primitivism focused on the European child.49 It gained strength in turn-of-the-century Vienna, where Sigmund Freud’s theories of psychoanalysis inspired the artistic climate.50 Through the production of their own toys, artists sought to access “the dark recesses of beginnings from which something like a proto-culture arises.”51 Marie von Uchatius, for instance, even produced her own Noah’s Ark set. Ultimately, their goal was to cure modern psychological ailments in adults by reconnecting with childhood. Spielzeug is a rare case in which the first form of primitivism teeters towards the second. Symmetrical to Bastian, who tasked himself with the responsibility of saving childhood from the destruction of modernity, Schmidt-Rottluff turned to the child to save man from the destruction of WWII. The toys conjured up a nature unplagued by old habits and trauma.

IV. Soft Masc after WWII

Schmidt-Rottluff wasn’t known for being childish. Rather, he was often described as large, manly, laconic, and discerning. The mixture of qualities yielded an air of mystery, which, depending on whom he encountered, was inspiring or intimidating. In this respect, he took after the midcentury “strong, silent” archetype, exemplified by Ernest Hemingway’s protagonists or those of Max Frisch.52 At the end of this section, I will challenge this image of Schmidt-Rottluff, arguing that slightness and reticence are blind spots in his traditional masculine reception.

Commentators often understood the tectonic and precise quality of Schmidt-Rottluff’s work to stem directly from his physical strength and silence respectively. Erika von Hornstein, who studied under Schmidt-Rottluff both before and after WWII, demonstrates this conflation of affect and composition in her earliest recollection of the artist:

He wore his mustard-colored beret deep over his brow and seemed to me large and powerful in his dark coat. His short-shaven mustache, his horn-rimmed glasses, his Slavic-shaped face with those high cheekbones—everything made me uneasy.

Even though his apartment was in the next neighborhood, he seemed to come far out of the distance. After his entry, the atmosphere in the studio quickly changed. A short round of greetings to all those who stood quietly by their easels. Schmidt-Rottluff went to the next closest student, gave him his hand, positioned himself in front of the image and looked. A while of nothing other than keeping silent and looking. At the same time, I saw how he rubbed both his thumbs against his other fingers and then raised his hands and built the composition by stroking his woven-together fingers through the air like a thick brush on canvas. What the teacher had to say was thereby said; even if words did follow, short and exact like the gestures.53

A photograph from 1962, found in the collection of Museum Wiesbaden, confirms that tensile strength and concentration were still central to the artist’s identity after the war.54 He hunches his shoulders, his brow, and focuses his attention. Due to the slight compression of his back and neck, the shot has the semblance of action—perhaps, the decisive pedagogical moment described by von Hornstein—but it is unmistakably highly staged. There are clear signs of careful preparation: his hair is neatly combed, his beard is freshly trimmed, and his shirt is tucked in. Suspense is built by how the camera peaks out coyly from behind the curtain, just like the cufflink from behind his sleeve. Formidable presence depends on self-presentation and how the image is framed, not just physical size.

Schmidt-Rottluff reentered public life after the war upon exhibiting fifty watercolors at the Schlossberg-Museum in Chemnitz (1946).55 It was his first show since his Berufsverbot [career prohibition] in 1942. The landscapes and still lifes, published in the exhibition catalogue Aquarelle aus den Jahren 1943-1946, give us an idea of how he spent the intervening years. There were many landscapes from the areas around his parents’ house, including the woods, mountains, and snow, as well as countless vegetables grown by Schmidt-Rottluff (Fig. 5).56 The countryside attests to the artist’s isolation, and the need to garden testifies to wartime food shortages. Gardening was an important means of supplementing meager rations.57

Adolf Behne, who had criticized Die Brücke in the 1920s,58 but fought to rehabilitate the old avant-garde after WWII,59 praised Schmidt-Rottluff’s manliness in the catalog. “What has captivated me for almost 40 years about Schmidt-Rottluff’s art, is its pure elemental draw to largeness/greatness, its inner most manly pride that hates everything small and small-minded, its human nobility that can only regard the truthful, the whole.”60 The heroic description would be better suited to a soldier in conflict rather than to a cultivator of root vegetables finding respite at his agrarian residence. Behne’s choice of the words pure and manly pride infelicitously echoes nationalist rhetoric. His argument posits a categorical distinction between Schmidt-Rottluff’s breed of manliness and anything small. This type of man hates the small so much that he can only see the large. This form of blindness misses the potential of metonymy, i.e. the small’s ability to stand in for the large. Such a claim is irreconcilable with the content of the watercolors: baby carrots, like small candy-corns, nestle together cutely in a bunch.61 Fresh crudité passed, somehow, for manly.

Other critics of the exhibition shared Behne’s judgments. Schmidt-Rottluff had become so automatically associated with the adjective groß (meaning both large and great) that it appeared in the titles of two more reviews: “A great (groß) artist and a courageous fighter for life” and “Chemnitz honors its great (groß) artist.”62 The hinge between the two meanings established Behne’s critical judgment: size was a sure path to success; presence—taking up more space—was privileged over absence. Despite the word’s imprecise meaning, Franz Karnoll applies it liberally throughout his review. For example, Schmidt-Rottluff’s “paintings, watercolors and woodcuts have been pulsating with a large (groß), manly feeling of strength since the beginning.”63

Karnoll tracks a series of identifications between the artist’s body and his work that build strength, like exercises. This notion of straining and releasing force differs from the sudden explosion, a common understanding of the energy in expressionism.64 In other words, he conceives of art as a domain where man’s virility can be stored and intensified. His argument becomes most alarming in the article’s last sentence: “here lies the largeness (Größe) of Schmidt-Rottluff’s art: she always searches for new paths and finds them and never lets herself be raped by any doctrine.”65 The callous compliment is even more offensive than Behne’s description: the reader is forced to think of Schmidt-Rottluff”s size as his natural defense against sexual assault.66 Both writers demonstrate psychic preoccupations with the war’s horrors. Try as they might to put the war behind them, they are incapable of employing nonviolent language. The inability of small motifs to demand a different language testifies to art’s limited autonomy and the constricted set of appropriate qualities (hypermasculine, aggressive, strong, proud, and laconic) at the time.

Claus Theweleit has identified sexual domination and wholeness to be constitutive factors of wartime male subjectivity.67 Behne and Karnoll’s violent terms of praise may have been acceptable during the war, but its further deployment afterwards risks writing over nondominant subjectivities thereafter. Objects and motifs from catalogue, such as ink bottles, miscellaneous shells, an odd book, sinuous cucumbers, and a twig from a chestnut tree, greatly deviate from their descriptions. These motifs are unmistakably small and perhaps weak. They are not heroic and virile, also not shattered or violated. They are, rather, resolutely ordinary.

In a letter from Spring 1946, Schmidt-Rottluff explained how he had become visually preoccupied with small things: “because God made all things with the same love, God can also be recognized in the smallest and slightest thing. Insofar is the How of the painted cabbage head of importance. Maybe the small things must bring us back belief and piety after the large ones have lost their symbolic strength.”68 The phrase, “the How of the painted cabbage head,” is Schmidt-Rottluff’s poetic counter to Behne. While Behne gives credit to the artist, Schmidt-Rottluff reverses the order of agency: the vegetables gave him tender strength. In the postwar era, since the large had lost its power, Schmidt-Rottluff decided to make himself vulnerable to the small. For the artist, this was due to God’s impartial love, whereas, for the critic, hatred of the small was art’s condition of possibility.

While the word “How” directs attention to form rather than content, the choice of cabbage is important, a vegetable renowned for its resilience, not assertiveness.69 Due to its tough outer layers, cabbage can readily withstand Germany’s unfavorable growing conditions; its crip texture and low sugar content also make it ideal for long-term pickling, a suited metaphor for laying low and waiting out the war’s hazardous conditions. It is precisely the need for a strong heroic figure, produced by the high tragedy of warfare, that occludes Schmidt-Rottluff’s soft reserve. These latter characteristics become visual in an untitled watercolor of cauliflower, found in the catalogue.70 Thick black contours safely mark out cute white faces from the gloom clouding around the lunch service. A small, localized region becomes a strategy for surviving the war.71 Just like how toy animals of Noah’s Ark toys counterbalance disheartening themes, i.e. human foibles and God’s wrath, a set of cheery, yet durable vegetables provide an alternative to the grave political climate.

Hearty vegetables are the not-to-be-forgotten context for Spielzeug. They firmly establish Schmidt-Rottluff’s turn towards childhood toys within a diversified practice of searching for and staking out small unaffected territories hidden within the large, damaged regions of German society. Whereas Bastian’s collecting project was deeply paternalistic, in which (the white European) man preserved endangered objects from humanity’s childhood, Schmidt-Rottluff searched for microcosms of innocence. In these places, his faith and unique form of soft masculinity could reticently live on.

Conclusion: Timelessness

Schmidt-Rottluff’s turn to childlike imagery occurred against the backdrop of a much larger public discourse, in which challenges of the Wiederaufbau concerning “guilt, German militarism, humanism, the concept of the nation, and postwar gender relations,” were metabolized in terms of youth and childhood.72 Jaimey Fisher, scholar of postwar education, identifies Ernst Weichert’s today little-known “Speech to the German Young” as one of the most popular addresses of the time.73 In contrast to other widespread public opinions that held youth accountable for active participation in Nazism, Weichert sanctioned youth off as a “constitutive alterity” that could become the “core of a regenerated, healthier society” after the war’s end.74 Schmidt-Rottluff’s interest in toys must be seen in the light of this debate on the guilt and innocence of youth.

Like many other commentators of the 1940s, Weichert repurposes the physical act of rebuilding the city as a metaphor for moral renewal: “And from the dust of your difficult path, you should dig up the truth and the justice and the freedom and erect before the eyes of the children the images, to whom the best of all times have looked up to.”75 Tactile verbs, like ausgraben [to dig] and aufrichten [to erect] evoke concrete images, grounding this lofty appeal to pathos. While Weichert sees humanist ideals, such as truth, justice, and freedom strewn amongst the rubble, Schmidt-Rottluff finds his old belongings. Just a few lines later, Weichert reconfigures chaos a new beginning, relying on the familiar biblical reference: “Noah’s Ark drifts towards the mountain out of every flood, the dove flies out of every ark and returns again with the olive leaf…We want to create a purer form, a purer image, and maybe once more bless the destiny, because it shattered a nation, so that a new crown can be forged.”76 Even though Schmidt-Rottluff’s rhetoric is subtler and humbler than Weichert’s grandiosity—a few toys and a small flower pot is far cry from a crown and destiny—the speech shows one potential danger of deploying Noah’s Ark as an allegory for the war: by calling for a purer future, Weichert risks reframing large-scale destruction and genocide as a process of cultural purification, an idea oddly aligned with the very Nazi ideology it seeks to oppose. Such a pitfall of the silver-lining is a good reason for Adorno’s resolute negativity. Perhaps there should have been nothing to look forward to.

In the fourth section of this essay, I reviewed Schmidt-Rottluff’s reception immediately before the moment when he excavated his old basement. This was a moment in history when art criticism mistook devotion to the non-dominant side of masculinity (small, unskilled, innocent, and weak) as exactly the opposite (large, masterful, virile, and strong). Critics extolled Schmidt-Rottluff’s toughness, braveness, and innate ability to see large universal forces, meanwhile he observed and described a world bereft of that very strength. Their conviction writes over his waxing infirmity, effectively drowning out his reticence.

Timelessness occurs most when the gradient reaches a null point across a swiftly moving perceptual terrain: when the collection dissolves into disorder. This can occur exclusively within the mind of the collector, when an individual object suddenly seems out of place, or the entire organizing logic no longer seems to make sense. Timelessness also occurs at the beginning of the komparativ-genetischen Methode, when a mess suddenly begins to look like a collection. After a brief period of looking, an observation is made, similarities and patterns are recognized, and some structured organization takes hold. These are the inklings after which man chases down his childhood.

As a 63-year-old man, Schmidt-Rottluff plunged headlong into timelessness when he decided to make a painting of children’s toys. In the historical moment beyond the painting, the physical elements of Spielzeug were picked out rubble and placed back into the collection. But the transition is captured within the picture itself in the way that two elephants and an atrophied third toy (that represents simultaneously one calf and two calves) make up only a very short, inconclusive line of pairs. Their stance head-to-toe is only a small and weak prelude of a greater organizational force yet to come.

Notes

1. Edward Said, nearly fifty years ago, critiqued similar assumptions about German orientalism, part of the German colonial imaginary, nearly fifty years ago: “There was nothing in Germany to correspond to the Anglo-French presence in India, the Levant, North Africa…Yet what German Orientalism had in common with Anglo-French and later American Orientalism was a kind of intellectual authority over the Orient within Western culture.” Edward W. Said, Orientalism. (New York: Vintage Books, 1979) 42.

2. Christian Weikop, “The ‘Savages’ of Germany: A Reassessment of the Relationship between Der Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke,” in German Expressionism: Der Blaue Reiter and Its Legacies, ed. DOROTHY PRICE, (Manchester University Press, 2020), 75–104.

3. Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983).

4. Tobias Rosen, “The Brücke-Museum is on Fire!” Texte zur Kunst, March 4, 2022, https://www.textezurkunst.de/articles/tobias-rosen-the-bruecke-museum-is-on-fire/.

5. Georg Lukács, “Größe und Verfall des Expressionismus,” Internationale Literatur, no. 1 (1934), 153-73.

6. Ettlinger, L. D. “German Expressionism and Primitive Art.” The Burlington Magazine 110, no. 781 (1968): 191–201. http://www.jstor.org/stable/875584.

7. Jill Lloyd, German Expressionism: Primitivism and Modernity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991).

8. Karl Ewald Fritzsch and Manfred Bachmann, Deutsches Spielzeug (Leipzig: Verl. für Kunst und Wiss., 1965), 50-56. Manfred Bachmann and Hans Reichelt, Holzspielzeug aus dem Erzgebirge (Dresden: Verlag Deutsch Kunst, 1984).

9. Christiane Remm, curator at the Brücke-Museum, speculates, “that the toys were found in his brother’s house in Chemnitz, Schmidt-Rottluff stayed there regularly. He had a niece, who was a kid in the 40s—as far as I know. It is also possible that he had acquired the toys as a gift for his niece. Or that he saw them in another family’s home, like I said, the figurines were very popular.” Christiane Remm, email to the author, January 19, 2021.

10. Theodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2018), 115.

11. “Sie sind Allegorien dessen, dass ein Exemplar oder ein Paar dem Verhängnis trotze, das die Gattung als Gattung ereilt.” Ibid. Theodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia, trans. Jephcott E. F. N. (New York: Verso, 1978), 150-52.

12. While both female and male African elephants have tusks, only male Asian elephants have tusks. Nonetheless, tusks are often considered markers of male gender in the popular imagination. It is impossible to determine if the toys in the painting are African or Asian elephants. Bernhard Blasskiewitz, Elefanten in Berlin (Berlin: Lehmanns Media, 2008), 8-9.

13. In one passage of Genesis, God specifies a pair of every animal, elsewhere, seven pairs of every animal. Mosche Blidstein, “How Many Pigs Were on Noah’s Ark?,” The Harvard Theological Review 108, no. No. 3 (2015): 448-70.

14. Roman Jakobson, Fundamentals of Language, trans. Moris Halle (The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter, 2002).

15. Martin Seel, “Minima Moralia. Reflexionen aus dem beschädigten Leben,” in Schlüsseltexte der Kritischen Theorie herausgegeben, ed. Axel Honneth (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2006), 34-37.

16. Jill Lloyd dates the beginning of Schmidt-Rottluff’s collecting of African masks to the time when Einstein’s book was first published in 1914. Although she does not explicitly argue that his collecting halted during the war, her research in the Brücke-Museum’s archive did reveal that almost all objects still in the collection today were acquired after 1945. Jill Lloyd, German Expressionism: Primitivism and Modernity (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1991), 380-85.

17. “Nur in der Irrationalität der Kultur selber, dem Winkel und Gemäuer, dem auch die Wälle, Türme, und Bastionen der in die Städte versprengten zoologischen Gärten zuzählen, vermag Natur sich zu erhalten. Die Rationalisierung der Kultur, welche der Natur die Fenster aufmacht, saugt sie dadurch vollends auf und beseitigt mit der Differenz auch das Prinzip von Kultur, die Möglichkeit zur Versöhnung.” W. Adorno, Minima Moralia; W. Adorno, Minima Moralia.

18. Aya Soika and Meike Hoffmann, Flucht in die Bilder? Die Künstler der Brücke im Nationalsozialismus (Berlin: Hirmer Verlag, 2019), 220

19. All translations are those of the author, unless otherwise noted. “Teppiche, Decken u. Malleinen, seltsamerweise alles noch vorhanden—Marie hat den Keller wie eine Löwin verteidigt. Küchengeschirr hat sich auch etliches angefunden, das M. gerettet hat—auch der Staubsauger—nur das Kabel ist mit verbrannt…Die Aquarelle waren noch vorhanden, wenn auch z. T. angeschimmelt, was aber noch zu entfernen war. Bilder sind ein Teil verschimmelt…3 Holzplastiken sind ebenfalls geblieben u. nicht verfeuert worden u. ein paar exotische Sachen. Leider ging eine Samoaschale kaputt—ich schicke sie Dir einmal, vielleicht kannst Du wenn Du mal Zeit hast, versuchen, sie zu leimen—es ist ein altes Stück.” Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Briefe nach Chemnitz, ed. Ralf W. Müller (Chemnitz: Chemnitzer Verlag, 2017), 76.

20. “Die Steinplatte ist Solnhofer—u. hier aus den Trümmern aufgeklaubt—ich hatte sie als Sockel für das Kälbchen verwendet—es stand ganz nett darauf.” Schmidt-Rottluff, Briefe nach Chemnitz, 75.

21. Solnhofer is a yellow-tan floor tiling used widely throughout Germany. Because the material is abundant in Bavaria, it was strongly promoted by the Nazis and liberally used in fascist architecture. Angela Schönberger discusses the material’s ruin value [Ruinenwert] in Abert Speer’s philosophy. Angela Schönberger, “The Thousand-Year Reich’s State Buildings as Predestined Ruins?,” in Tumbling Ruins, ed. Matthias Klieford (Berlin: Distanz, 2021).

22. Ralf W. Müller in Schmidt-Rottluff, Briefe nach Chemnitz, 76.

23. Lloyd, German Expressionism, 71 and fn. 24, 242.

24. In the late 1940s, a large number of films were made in the Trümmerfilm [rubble film] genre. Jaimey Fisher, “Who’s Watching the Rubble-Kids? Youth, Pedagogy, and Politics in Early DEFA Films,” New German Critique, no. 82 (2001): 91-124.

25. “[A]b Mai 1945 kein Bruch, kein Neuanfang, keine ‘Stunde Null’, sondern Kontinuität seit spätestens den 1920er Jahren.” Hoffman, Flucht in die Bilder, 237-240.

26. Kea Wienand poses this question for postwar artists, but does not discuss how primitivism was also sustained by the older generation who taught after the war. Kea Wienand, Nach dem Primitivismus? Künstlerische Verhandlungen kultureller Differenz in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1960-1990. Eine postkoloniale Relektüre, ed. Sigrid Schade and Silke Wenk, Studien zur visuellen Kultur, (Bielfeld: transcript Verlag, 2015).

27. Ann Laura Stoler, “Imperial Debris: Reflection on Ruins and Ruination,” Cultural Anthropology 23, no. 2 (2008): 191-219.

28. W. G. Sebald, Luftkrieg und Literatur (Berlin: Carl Hanser Verlag, 1999).

29. Stoler, “Imperial Debris,” 206.

30. Patricia Purtschert’s also discusses ‘human zoo’ as an imperial ruin. Patricia Purtschert, “The return of the native: racialised space, colonial debris, and the human zoo,” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 22, no. 4 (2014): 508-23.

31. Thomas M. Lekan writes, “colonial nostalgia transformed West Germans from the “good colonizers” of 1900 into the globally minded conservationists of 1960 without confronting the imperialist legacies that had shaped their longings for wild Africa in the first place.” Thomas M. Lekan, Our gigantic zoo: a German quest to save the Serengeti (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2020).

32. Bernhard Gissibl, The nature of German imperialism: conservation and the politics of wildlife in colonial East Africa (New York & London: Berghahn Books, 2016).

33. Hans Paasche, “Kolonie oder Zoologischer Garten,” Deutsch-Ostafrikanische Zeitung March 3, 1907, 3.

34. Fear of elephants is widespread in colonial literature, for example: George Orwell, “Shooting an Elephant,” 1936, accessed March 20, 2021, https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/shooting-an-elephant/.

35. Grzimek won an Oscar for his documentary on the Serengeti. Serengeti darf nicht sterben, directed by Prof. Dr. Berhard Grzimek (1959, Berlin: Family Entertainment, 2009), DVD.

36. Bernhard Grzimek, “Der Wiederaufbau des Frankfurter Zoos,” in Auf den Mensch gekommen (Munich: Bertelsmann Verlag, 1974), 179-215.

37. Lekan, Our Gigantic Zoo, 41.

38. In 2001, the Brücke-Museum made the approximately 100 objects in Schmidt-Rottluff’s collection available for inline viewing and research: “Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s Collection of Objects from Colonial Contexts in the Brücke-Museum Berlin,” Wikimedia Commons, las accessed March 10, 2024, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=Category:Karl_SchmidtRottluff%27s_Collection_of_Objects_from_Colonial_Contexts_in_the_Brücke-Museum_Berlin&oldid=730425970&uselang=de.

39. This question is aimed at seemingly innocent objects, ones that cannot be restituted or considered ‘touristy,’ collected at “markets or from living artists who specialized in the production of copies of African pieces corresponding to the tastes of Europeans.” Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics (Paris: Ministère de la Culture, 2018), 27-41, 58.

40. Charlotte Klonk, “Non-European Artifacts and the Art Interior of the Late 1920s and Early 1930s,” in Interiors and Interiority, ed. Ewa Lajer-Burcharth and Beate Söntgen (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016), 211-25.

41. Emil Nolde, for example, observed the frenzy of objects both in painting and writing. Jill Lloyd, “Emil Nolde’s Drawings from the Museum für Völkerkunde,” The Burlington Magazine 127, no. 987 (1985): 380-5

42. “Im größten Spielzeugwarenlager, im buntesten Antiquitätengewölbe, im dicht gestellten Naturalienkabinett kann es nicht unübersichtlicher, magazinartiger und muffiger sein. Unerhörte Reichtümer, Milliardenwerte, kostbare Seltenheiten sind so neben- und hinter-, vor- und übereinander aufgestellt, daß man sie fast zu hassen beginnt. Man kann nichts einzeln sehen, es herrscht ein solches Gedränge, daß nur Fachgelehrte die Fassung nicht verlieren. Viele Gegenstände sind gleich zu Hunderten da…planmäßig geordnet, und dennoch scheinbar wirr durcheinander geworfen erblickt man Opfergeräte, Landkarte, Abgüsse von Reliefs (gleich hundert Meter lang), Kleiderpuppen, Musikinstrumente, Fayencen und Kacheln, Bilderbücher, Kinderspielzeug…” The book’s title refers to the intense debate inside the museum about its antiquated exhibition strategy and has no direct relation to the World Wars. Karl Scheffler, Berliner Museumskrieg (Berlin: Cassirer, 1921), 20.

43. “The hardly overseeable and densely packed fill of the Völkerkunde Museums are due – in Paris as in Berlin – not in the first place to the limited space of the individual museum buildings, but date back more so to the contemporary methodological principles of ethnographic and ethnological presentation.” Uwe Fleckner, Carl Einstein und sein Jahrhundert. Fragmente einer intellektuellen Biographie (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2006).

44. Under Voß’s leadership from 1874 to 1906, the museum acquired over 84,000 items. Tobias Gärtner, “Begründer einer international vergleichenden Forschung—Adolf Bastian und Albert Voß,” Praehistorica et Archaeologica 36/37 (2004/2005): 88.

45. “Die zu untersuchenden Erscheinungen werden innerhalb der ihnen ähnlichen bei denen eingereiht, mit welchen sie die meiste Verwandtschaft zeigen. Die auf solche Weise gewonnen Reihen verwandter Erscheinungen werden dann nach dem Grade ihrer Verwandtschaft gruppiert und wieder unter sich verglichen, um zu ersehen, ob und inwieweit sie gemeinsamen Ursprungs sind, welchen Einflüssen sie ihre Verschiedenheiten verdanken und ob sich die eine Reihe vielleicht aus der anderen entwickelt hat…Je größer nun die Zahl dieser Beobachtungen wird und je umfassender und ausgedehnter das Material das zur Vergleichung herangezogen werden kann, um so mehr Schlüsse lassen sich aus demselben ziehen und, je öfter sich gleichartige Beobachtungen wiederholen, desto sicherer wird die Annahme ihrer Richtigkeit.” Albert Voß in Sigrid Westphal-Hellbusch, “Hundert Jahre Museum für Völkerkunde Berlin. Zur Geschichte des Museums,” https://www.digi-hub.de/viewer/image/1499062302477/ (Baessler-Archiv, 1973), 3.

46. “Das Ergebnis dieser Neugestaltung ist, daß die einzelnen Sammlungsstücke nun als eigenständige Objekte wahrgenommen werden, und der Betrachter ist nicht länger dazu angehalten, die Artefakte als bloße Belege in eine lange Reihe von Vergleichswerken einzugliedern.” Fleckner, Carl Einstein und sein Jahrhundert. Fragmente einer intellektuellen Biographie, 300.

47. Hicks Dan, “Necrology,” in The British Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Restitution (Pluto Press, 2020, 152-165.

48. Eine Zeit, wie die unsrige, welche mit rauher Hand zahlreiche Urstämme vernichtet und die Oberfläche der Erde in allen Richtungen durchfurcht, ist es den nachkommenden Generationen schuldig, so viel wie möglich von dem zu erhalten, was für das Verständnis der Entwicklung des Menschengeistes noch aus der Periode der Kindheit und der Jugend der Menschheit übrig geblieben ist. Was jetzt zerstört wird, ist für die Nachwelt unrettbar verloren.” Westphal-Hellbusch, “Hundert Jahre Museum für Völkerkunde Berlin. Zur Geschichte des Museums,” 3-4.

49. Jo Alice Leeds, “The History of Attitudes toward Children’s Art,” Studies in Art Education 30, no. 2 (1989): 93-103.

50. Megan Brandow-Faller, “‘An Artist in Every Child—A Child in Every Artist’: Atistic Toys and Art for the Child at the Kunstschau 1908,” West 86: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 20, no. 2 (2013): 195-225.

51. Ibid., 198.

52. Frank Sitotich et al., “Yearning to Break Silence: Reflections on the Functions of Male Silence,” in Troubled Masculinities, ed. Ken Moffatt (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2012); Teodóra Dömötör, “Anxious Masculinity and Silencing in Ernest Hemingway’s ‘Mr. and Mrs. Elliot’,” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies 19, no. 1 (2013): 34-38; Max Frisch, Homo faber (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1977).

53. “Er trug eine senffarbene Baskenmütze in die Stirn gezogen und erschien mir in seinem dunklen Mantel groß und kraftvoll. Sein kurzgestutzter Bart, seine Hornbrille, sein slawisch modelliertes Gesicht mit den hohen Wangenknochen, alles machte mich beklommen. ¶ Obwohl seine Wohnung im nächsten Stadtviertel lag, schien er aus weiter Ferne zu kommen. Mit seinem Eintritt veränderte sich augenblicklich die Atmosphäre im Atelier. Ein knapper Gruß an alle ringsum, die verstummt an ihren Staffeleien standen. Schmidt-Rottluff trat zum Nächststehenden, gab ihm die Hand, stellte sich vor das Bild und schaute. Lange nichts als Schweigen und Schauen. Dabei sah ich, wie er beide Daumen mit den übrigen Fingern aneinanderrieb, dann die Hand hob und mit zusammengelegten Fingern wie mit einem Borstenpinsel vor der Leinwand in der Luft die Fläche hinstrich, die Komposition zurechtbaute. Was der Lehrer zu sagen hatte, war damit gesagt, auch wenn noch Worte folgten, knapp und genau wie die Gesten.” Erika von Hornstein, So blau ist der Himmel. Meine Erinnerung an Karl Schmidt-Rottluff und Carl Hofer (Berlin: Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1999), 9.

54. The photograph can be at the following website: https://sammlungziegler.de/portfolio/karl-schmidt-rottluff/.

55. Despite his Berufsverbot, which restricted his sale and instruction of painting, Schmidt-Rottluff did, in fact, paint during the war and even sold some of the works in private. Yet, aside from painting one small still life and a self-portrait in oil, he painted almost exclusively in watercolors at this time. Soika and Hoffmann, Flucht in die Bilder? Die Künstler der Brücke im Nationalsozialismus, 165-7.

56. “Karl Schmidt-Rottluff: Aquarelle aus den Jahren 1943-1946,” ed. Schloßberg-Museum Städtische Kunstsammlung zu Chemnitz (Chemnitz: Lederbogen, 1946).

57. Karl and Kurt Schmidt-Rottluff wrote about the availability and prices of staples, like butter or milk, in addition to their success or failure with certain crops. Schmidt-Rottluff, Briefe nach Chemnitz; Schmidt-Rottluff, Briefe nach Chemnitz.

58. Adolf Behne, Moderne Zweckbau (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1998), 34-38.

59. Behne’s postwar support for die Brücke artists was a complete reversal of his earlier disapproval during the height of his critical prowess Adolf Behne, “Entartete Kunst,” in Schriften zur Kunst (Berlin: Mann Verlag, 1998), 179-221. John-Paul Stonard discusses the greater political reasons for these shifts: John-Paul Stonard, Fault Lines: Art in Germany 1945-1955 (London: Ridinghouse, 2007), 177-81.

60. “Was mich seit bald 40 Jahren an die Kunst Schmidt-Rottluffs fesselt, das ist ihr reiner elementarer Zug zur Größe, ihr innerster männlicher Stolz, der alles Kleinliche, Kleine tief verachtet, ihr menschlicher Adel, der nur das Wahrhaftige, das ganze achten kann.” “Karl Schmidt-Rottluff: Aquarelle aus den Jahren 1943-1946,” 8.

61. Sianne Ngai raises the possibility that hatred might be the rejection of a threat posed by the small and cute. “[I]t is possible for cute objects to be helpless and aggressive at the same time. Given the powerful affective demands that the cute object makes on us, one could argue that this paradoxical doubleness is embedded in the concept of the cute from the start.” Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 85.

62. Franz Karnoll, “Professor Schmidt-Rottluff: Ein großer Künstler und ein tapferer Lebenskämpfer”; H. Sch. [author’s full name unknown], “Chemnitz ehrt seinen großen Maler: Eröffnung der Ausstellung Karl Schmidt-Rottluff im Schloßbergmuseum.” Both In: Unknown, SMB-ZA, Künstlerdokumentation, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.

63. “Seine Gemälde, Aquarelle und Holzschnitte sind von Anfang an von einem großen männlichen Kraftgefühl durchpulst.” Karnoll, “Ein großer Künstler.” Karnoll, “Professor Schmidt-Rottluff: Ein großer Künstler und ein tapferer Lebenskämpfer.”

64. Wilhelm Worringer, Abstraktion und Einfühlung (München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2007).

65. “Darin liegt die Größe der Kunst Schmidt-Rottluffs, daß sie immer neue Wege sucht und findet und sich von keiner Doktrin vergewaltigen läßt.” Karnoll, “Ein großer Künstler.” Karnoll, “Professor Schmidt-Rottluff: Ein großer Künstler und ein tapferer Lebenskämpfer.”

66. Karnoll published a second small article about the exhibition, which also intermixed sexual and violent metaphors. With reference to a drab winter landscape, he describes how the earth’s inner juices seek liberation and ruin their surroundings in the process. “Wir meinen, alle Kräfte und Säfte der Erde dampften und strömten aus dem innersten Kern heraus und Energien suchten Befreiung, die dabei ein anderes Stück Leben zerstören und vernichten müssen.” Franz Karnoll, “Die Bilder von Schmidt-Rottluff.”In: Unknown, SMB-ZA, Künstlerdokumentation, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.

67. Claus Theweleit, “‘Through the body…,” in Male Phantasies Volume 1: Women, Floods, Bodies, History (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 107; Claus Theweleit, “The Whole,” in Male Phantasies: Psychoanalyzing the White Terror (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 389

68. “Da Gott alle Dinge mit gleicher Liebe gemacht hat, kann auch im kleinsten und geringsten Ding Gott erkannt werden. Insofern wird das Wie des gemalten Kohlkopfes von Belang. Vielleicht müssen uns die kleinen Dinge den Glauben und das Frommsein wiederbringen, nachdem die großen ihre Symbolkraft verloren haben.” Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, ‘Ungemalte Bilder’ von 1934 bis 1944 und Briefe an einen jungen Freund, ed. Gunther Thiem (München: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2002), 138.

69. Frederic Jameson reminds us that in some cases “content seems to somehow contaminate form.” Here, he refers to Naturalism: “the Germans used to say that it ‘stank of cabbage’; that is, it exuded the misery and boredom of its subject matter, poverty itself.” While Jameson disparages both Naturalism and the vegetable, Schmidt-Rottluff reappraises the latter as humble and noble.

70. Both cabbage and cauliflower belong to the Brassica Olecacea family, a relatedness made visible by their German names: Kohl and Blumenkohl.

71. Other commentators understand the domestic settings of his postwar paintings, especially those produced during the Berlin Blockade, as expressions of loneliness, isolation, and recession away from society. Karl Schmidt-Rottluff: die Berliner Jahre 1946-1976, ed. Magdalena M. Moeller (München: Hirmer Verlag, 2005), 86-87.

72. Jaimey Fisher, Disciplining Germany: Youth, Reeductation, and Reconstruction After the Second World War (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2007), 4-5.

73. Ernst Weichert, Rede an die deutsche Jugend 1945 (München: Zinnen-Verlag, 1945).

74. Fisher, Disciplining Germany: Youth, Reeductation, and Reconstruction After the Second World War, 167.

75. “Und ihr sollt die Wahrheit wieder ausgraben und das Recht und die Freiheit und vor den Augen der Kinder die Bilder wider aufrichten, zu denen die Besten aller Zeiten emporgeblickt haben aus dem Staub ihres schweren Weges.” “Weichert, Rede an die deutsche Jugend 1945, 39.

76. Aus jeder Sintflut treibt die Arche dem Berge zu, aus jeder Arche fliegt die Taube und kehrt mit dem Ölblatt wieder…Eine reinere Form wollen wir schaffen, ein reineres Bild, und einmal vielleicht werden wir das Schicksal segnen, weil es ein Volk zerbrach, damit aus den Trümmern eine neue Krone geglüht werde.” Ibid., 4