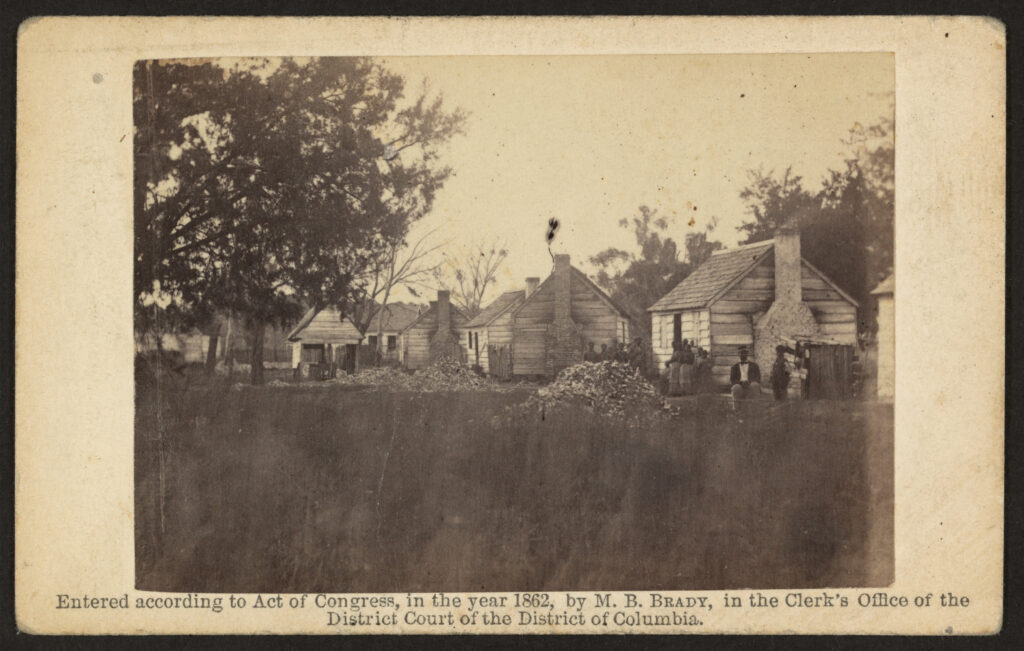

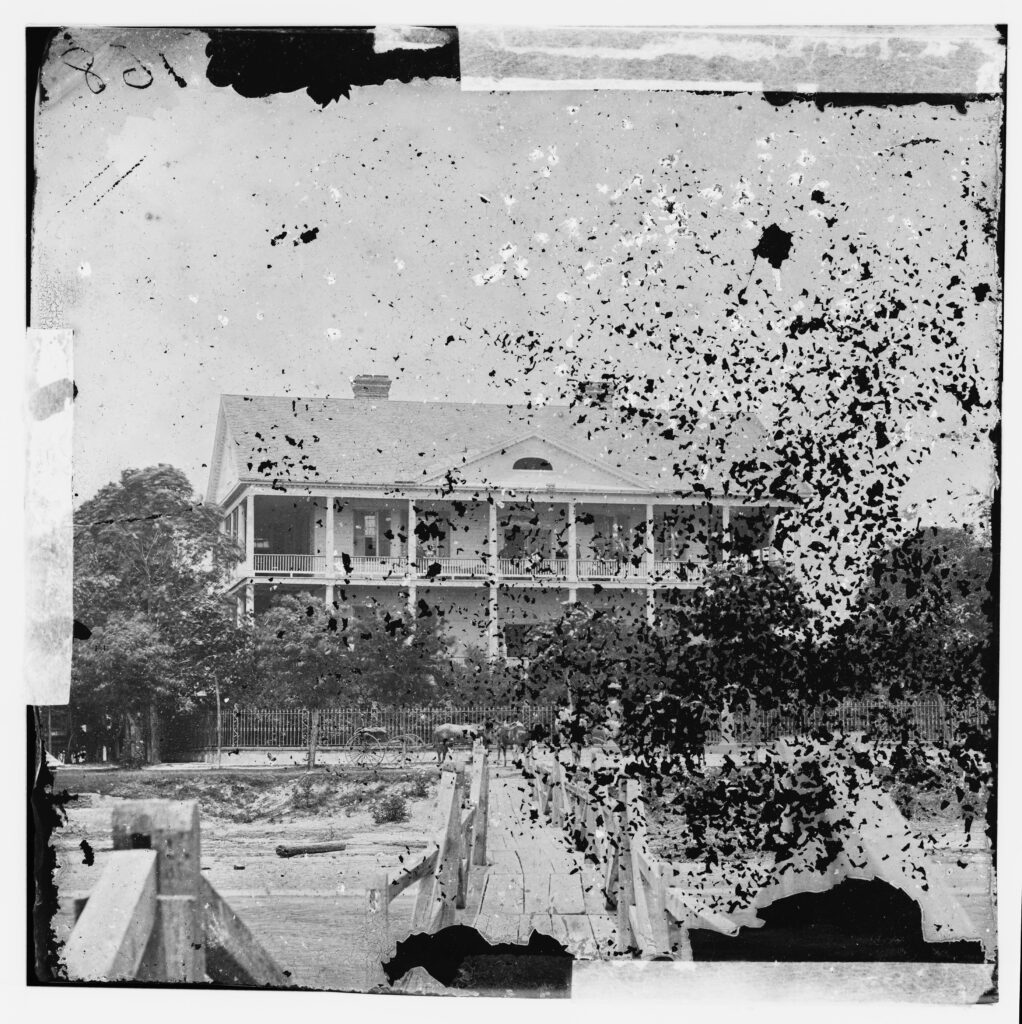

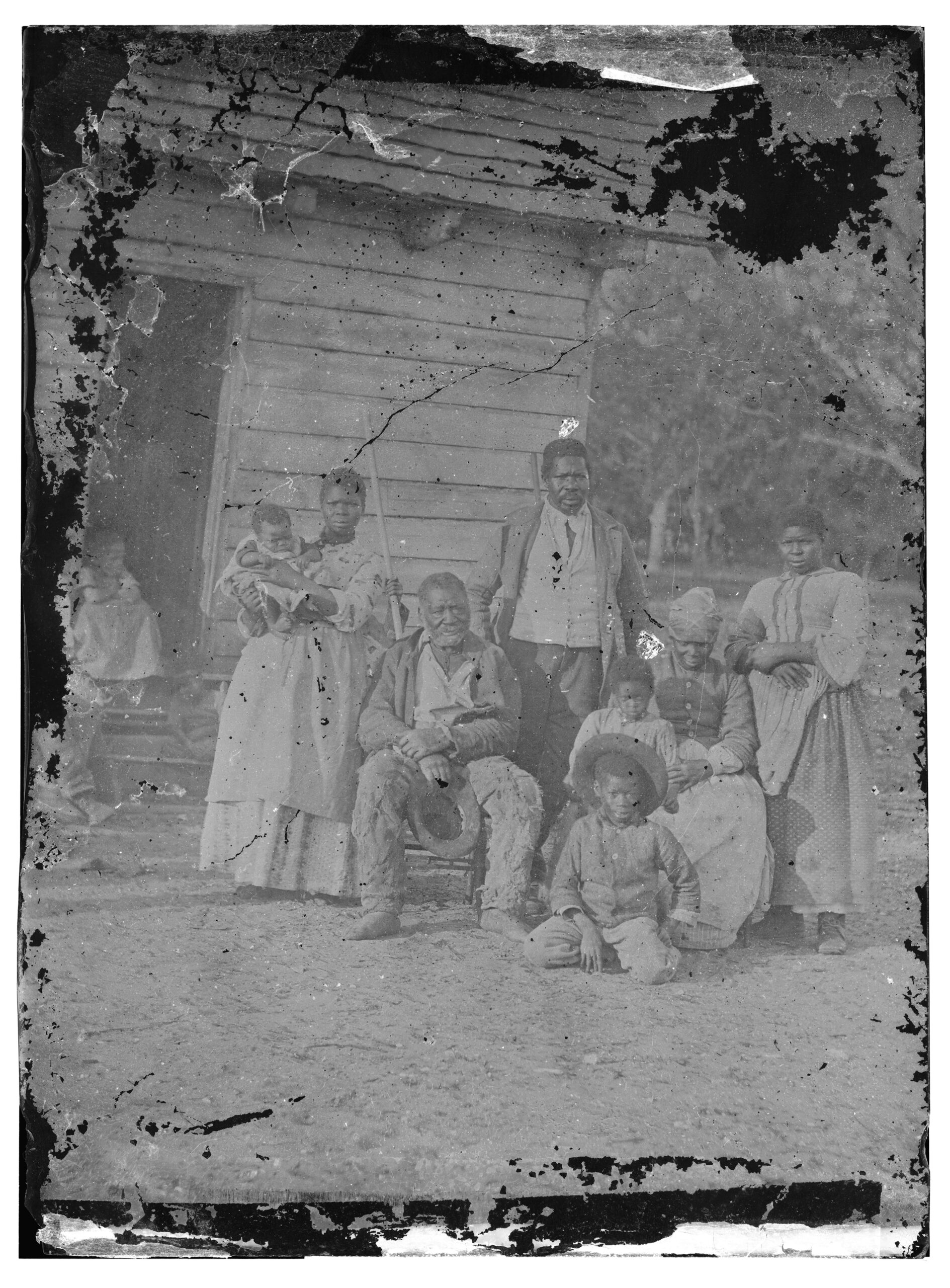

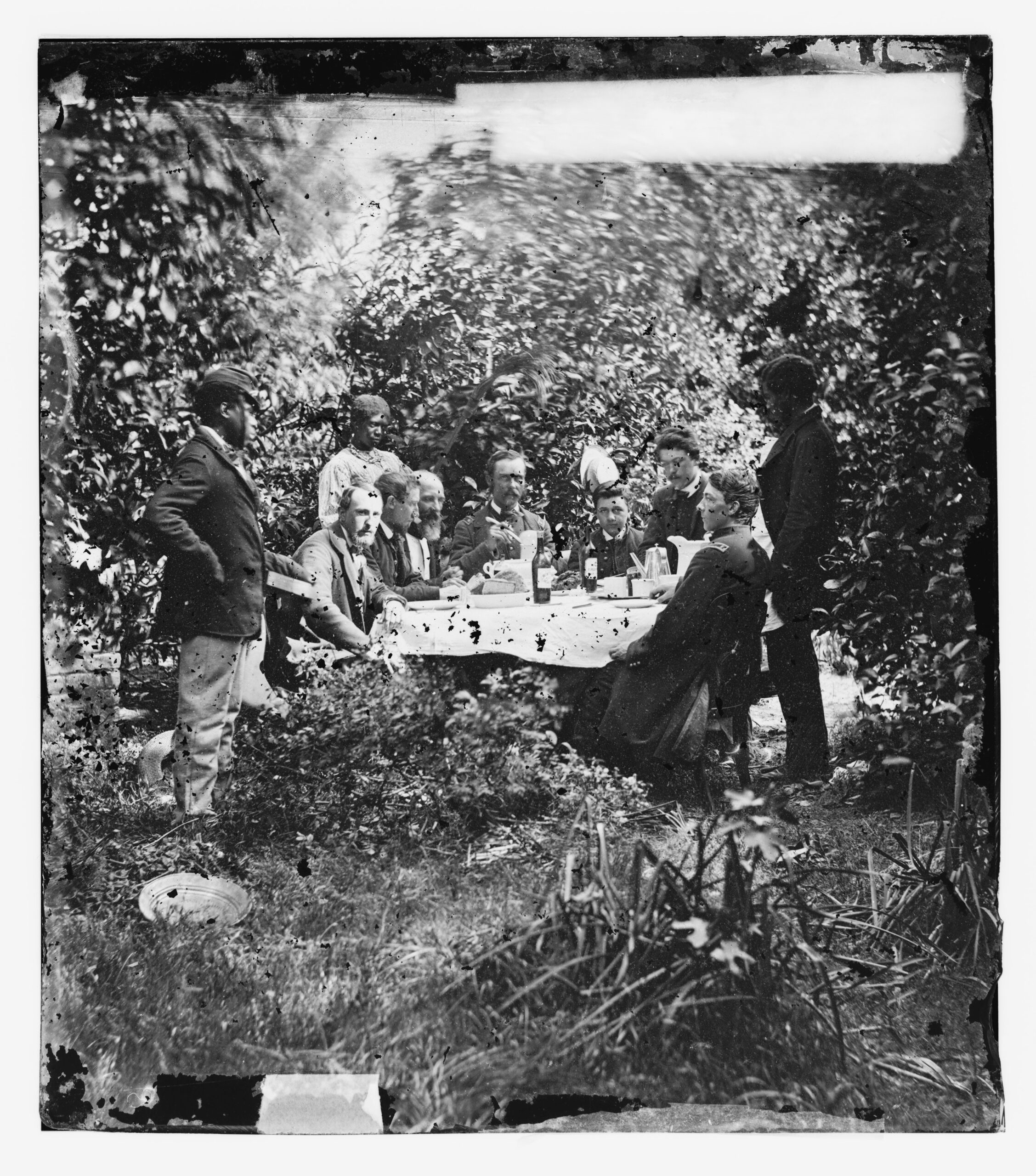

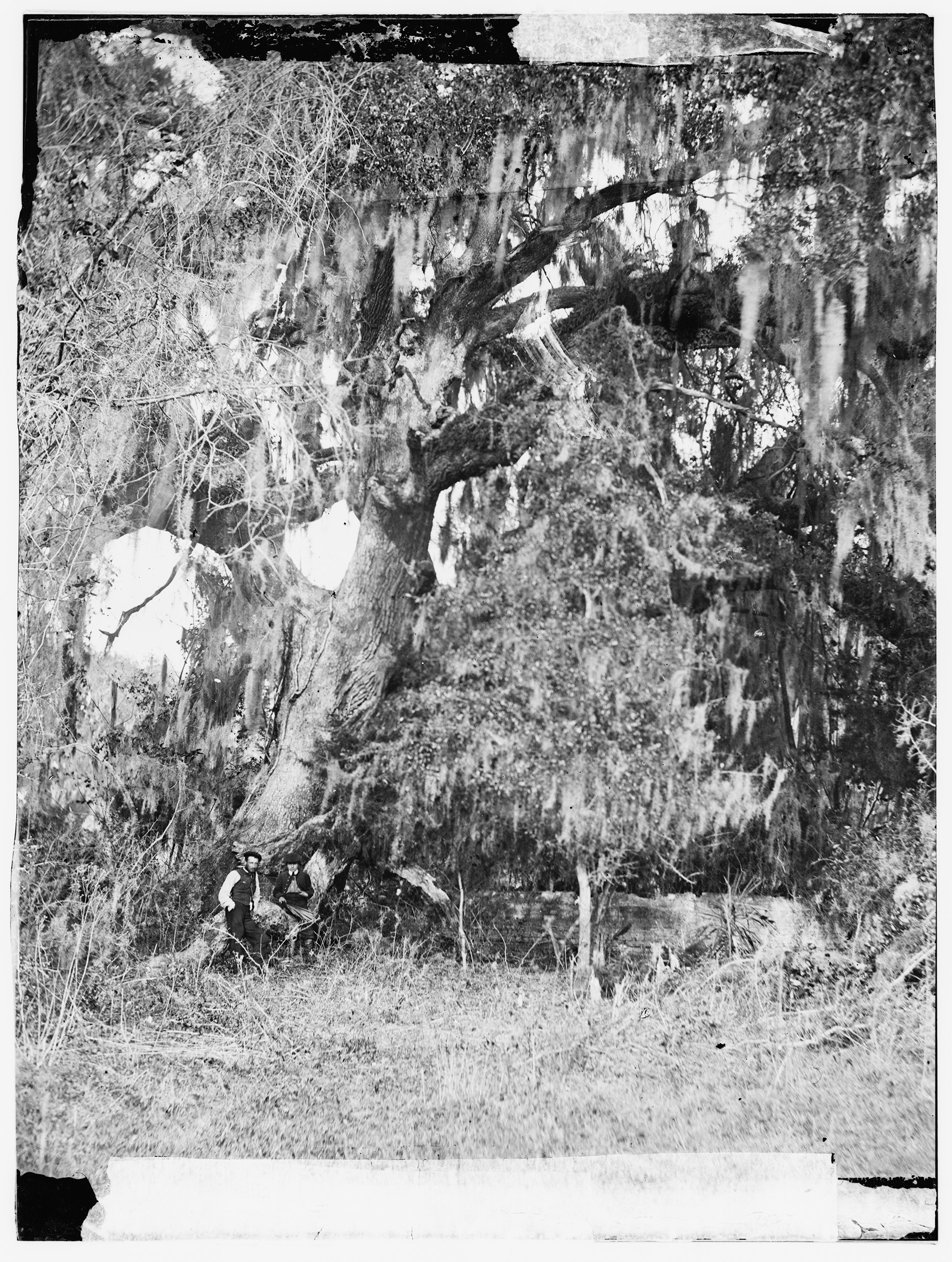

Consider a photograph taken by Timothy H. O’Sullivan in 1862 (Fig. 1). In that corner of a cotton plantation apportioned to the homes of those who were forced to labor on it, the photographer set up his camera and portable darkroom, and exposed a collodion-coated glass plate to the light. O’Sullivan (ca. 1840-1882) arrived in Port Royal, South Carolina, in April, some five months after the Union Navy bombarded Port Royal Sound and prompted the surrounding Sea Islands’ white inhabitants, among the wealthiest cotton planters in the country, to flee.1 The people those planters had enslaved—the people in this photograph—stayed where they were, setting their emancipation in motion by refusing to move. Their steady gazes toward the camera make clear that they knew the photographer was there, but the distant view suggests that he entered their living space, or stood at its edge, without their permission or encouragement. On the image’s right margin, someone hovers in a doorway, the glint of light on a forehead just barely discernable—the person in the house captured in the act of not being seen. The light reflected off their body left only the slightest shadow on the collodion emulsion coating O’Sullivan’s glass-plate negative (Fig. 2). When O’Sullivan’s employer, Mathew Brady, printed the image for sale on card later that same year, it was cropped to give a tighter view of the central figures, erasing this moment of refusal and collapsing the uneasy distance between photographer and subjects (Fig. 3). The negative retains evidence of a more complicated encounter.

Among the first enslaved people in the South to be liberated by Union soldiers, Black residents of Port Royal, Beaufort, and the surrounding Sea Islands became, in the eyes of white Northern observers, ciphers for the possibilities conjured by the end of bondage.2 At the time when O’Sullivan took his photographs, prior to the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, the formerly enslaved in Union-occupied territory existed in the nebulous legal position of “contraband of war,” a status still rooted in enslavement’s commodification of their personhood.3 Photographs of the Sea Islands, though a small subset of the vast corpus of Civil War photography, constitute perhaps the most extensive surviving visual record of wartime emancipation in the South. Even after the war’s end and the abolition of slavery throughout the former Confederacy, the Sea Islands retained their importance as case studies in the unfolding experiment of emancipation. In January 1870, for instance, J.W. Alvord, an abolitionist minister then working for the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (Freedmen’s Bureau), wrote to his superiors in Washington: “On Sea Island plantations I had excellent opportunity of seeing the Freedmen’s condition.”4 His phrasing—“seeing the Freedmen’s condition”—reflects the critical importance of the visual in this project of social assessment.

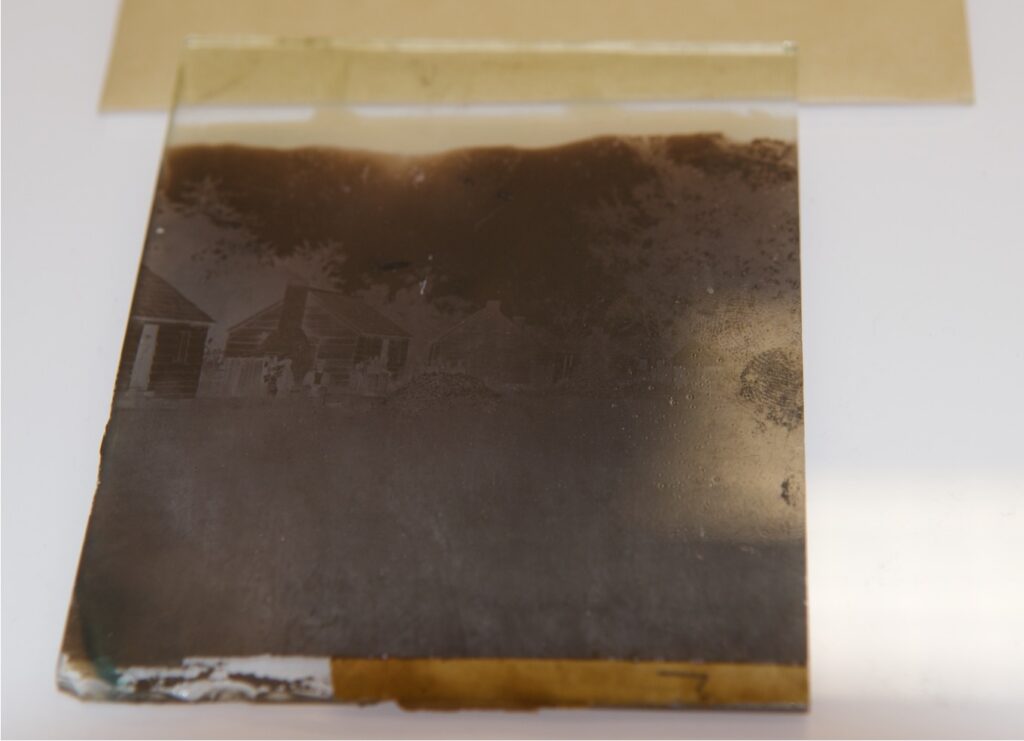

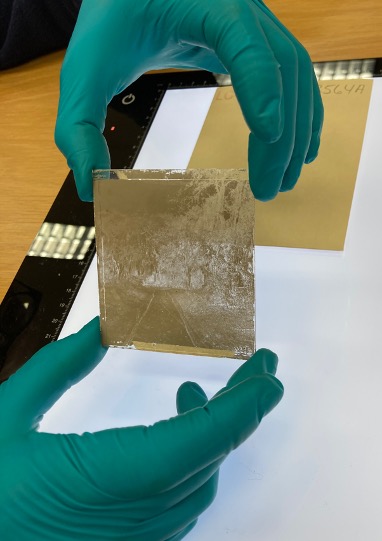

Yet whatever information O’Sullivan’s Sea Islands stereographs may have conveyed to viewers in 1862, the condition in which they appear today is one of near illegibility. Aside from the 1862 card, none of the images I discuss here are, in fact, printed photographs. They are glass-plate collodion negatives, from which positive prints do not survive or were made long after the war (Fig. 4). The negatives were scanned to make digital positives by the Library of Congress, which holds much of O’Sullivan’s wartime work (Fig. 5). (I reproduce some of these digital positives for ease of viewing.) To see the images on the actual negatives requires a curator’s manipulation of the objects on a light table, and even then, they are difficult to decipher (Fig. 6). From most angles, the surface of the negative presents only a graphite-colored sheen, sometimes mottled by chemicals or pocked by particles and fingerprints. The passage of time has left marks: abraded collodion surfaces, chipped and broken glass plates. This damage also reflects the objects’ long sojourn outside of archival care. Most of O’Sullivan’s wartime negatives belonged to his employer, Brady, who found himself in debt after the war and sold most of his inventory to the publisher E. & H.T. Anthony. The negatives then passed through the hands of multiple publishers and collectors, before being placed in storage in Washington in 1916.5 Not until 1943 were the boxes of some 7,500 original glass negatives and 2,500 copy negatives uncovered and purchased by the Library.6

The literal disappearance of these objects underscores the negative’s status as the “repressed, dark side of photography,” unvalued and inconsistently acknowledged in the history and theory of the medium.7 The embodied experience of looking at glass-plate negatives—contending with their age, their fragility, their opacity, their obdurate thingness—is markedly different from the experience of looking at positive prints or digital images. Tina M. Campt writes that viewing a negative requires attunement to a “spectral photographic presence,” to “shadow in the darkness of the emulsion.”8 If photographic positives confirm the visual facticity of the world, negatives capture a world that is evanescent, alien, and otherwise. Formed by the action of light reflected from the represented object onto photosensitive chemicals, negatives are, in a truer sense than photographic positives, materially indexical to their referents.9 Yet they lack the appearance of truth to nature usually presumed to accompany indexical representation. (Stereographic negatives literally offer two slightly different versions of the same scene, further straining the idea of truthfulness.) Thus, as Campt writes, “The materiality of the photo secures neither its indexical accuracy nor transparency; it leads us to question it instead. It exposes our own investments in the visual as evidence.”10 At least for the moment of encounter, the negative cleaves seeing from knowing.

Contemporary theorists have wrestled with the negative’s strangeness, but so too did nineteenth-century writers on photography, as negative-positive processes succeeded the daguerreotype in the middle of the century. As Jennifer Raab argues, the post-Civil War period in the United States saw the embrace of the cultural, even legal, validity of photographs as witnesses, testimony, and evidence.11 Yet if the photographic positive increasingly bore the imprimatur of truth, the photographic negative retained the capacity to obscure it. Writing in the Atlantic in 1859, doctor and essayist Oliver Wendell Holmes described the negative as “perverse and totally depraved…where the light of the eye was darkness, and the deepest blackness was gilded with the brightest glare.”12 Illegible, even immoral in its flagrant distortion of the truth, the negative disturbed some of the nineteenth century’s basic assumptions about photography.13

In the particular context of wartime Reconstruction, investment in the evidentiary capacities of the photographic intersected with the white public’s investment in “seeing the…condition” of the freed Black subject. O’Sullivan’s photographs of the Sea Islands document families, homes, land use, and labor: aspects of emancipated life that were of profound interest to Northern officials, teachers, missionaries, reformers, and businessmen during this period. But the negatives that gave rise to those images—which are the photographic objects that survive in the archive—solicit a different kind of looking and perform a different kind of work. Contending with the negative’s refusal to be evidentiary, to offer “accuracy” or “transparency,” is a condition of viewing the photographs now: a problem that opens an aperture of possibility, a way of seeing otherwise.

Both in terms of its role in the photographic process and its interpretive possibilities, the negative is a generative rather than conclusive object. It is almost impossible to ascribe to any of these negatives a single intention or reception. O’Sullivan never wrote about his visit to the Sea Islands and the photographs he made there; I have found no record of viewers’ responses to them, nor any sitter’s recollection of the experience of being photographed. Much about these images—the sitters’ names, for instance—is unknown and now, perhaps, unknowable.

In this article, I seek to remain with, rather than resolve, this instability and uncertainty; to dispense with any claim to read these images exhaustively. The article moves outward in space and time: from the photographed bodies, families, and homes of the freed in 1862 to the land on which they stood, its history, and its future. I conclude by turning to the chemical substrate of the negatives and their material links to cotton and chemical industry in the post-Reconstruction life of the Sea Islands. In writing these histories, I have thought of performing an oscillation, as if shifting the negative so that it flickers back and forth, between past and future, between the elusive image and the darkened slick of chemicals that coats the glass surface. If the stereographs were intended to provide evidence of their subjects’ “condition,” I ask: what conditions do these negatives materialize?

Evidence and Burden

Photographs of emancipated people on the Sea Islands may have circulated among the Northern public both during and after the Civil War. Thirty-five of O’Sullivan’s stereographs were offered for sale by Mathew Brady in 1862 as “Plantation and Camp Scenes, Beaufort, S.C.,” “Port Royal Island Scenes,” and “Scenes at Hilton Head, S.C.” A nearly identical set was sold by Alexander Gardner in 1863 as “Illustrations of Sherman’s Expedition to South Carolina.”14 Alongside O’Sullivan, the white photographers Henry P. Moore, Samuel A. Cooley, and Hubbard & Mix all produced images of the Sea Islands in the 1860s.15 We cannot know to what degree the freedpeople felt themselves free to dictate the terms of their appearance in such photographs or to refuse to be photographed at all. Imbalances of power riddled these encounters in the visual field, imbalances rooted in race, war, and history, but also in the basic distinction between photographer and photographed. A stereograph made sometime between 1861 and 1865 by one of these photographers, Samuel A. Cooley, offers a vivid performance of the unequal distribution of labor, agency, and visibility in photographic practices of the Civil War period (Fig. 7). Cooley’s name appears twice, prominently advertised in the banners decking his equipment wagons, as a group of white men, presumably including Cooley himself, pose with leisured confidence around a camera. The two Black men who appear in the image are unnamed figures, consigned to the left margin and the background, their manual labor driving the photographer’s wagons essential to, but separated from, the creative work of making photographs.

The status of the newly emancipated as what Nicholas Mirzoeff has termed “visual subjects” was thus fraught with as many ambivalences as was their status as civil and political subjects.16 As Mirzoeff argues, “visual subjects” are participants in complex, historically conditioned dynamics of seing and being seen—surveilling and being surveilled, observing and being observed, knowing and being known—that are enmeshed within the operations of social power.17 Enslavement had long involved the exercise of power in the visual field and enabled some of nineteenth-century photography’s most coercive practices.18 The era of emancipation brought different, though still powerful, imperatives to the depiction of Black sitters. As Saidiya V. Hartman has argued, freedom placed upon the freedpeople’s own shoulders the burden of earning civic, political, and social participation, of proving their right to have rights—a proof that could take the form of visual evidence.19 This visibility constituted one facet of what Hartman terms the “burdened individuality” of the newly freed, their “duty to prove their worthiness for freedom rather than the nation’s duty to guarantee, at minimum, the exercise of liberty and equality.”20

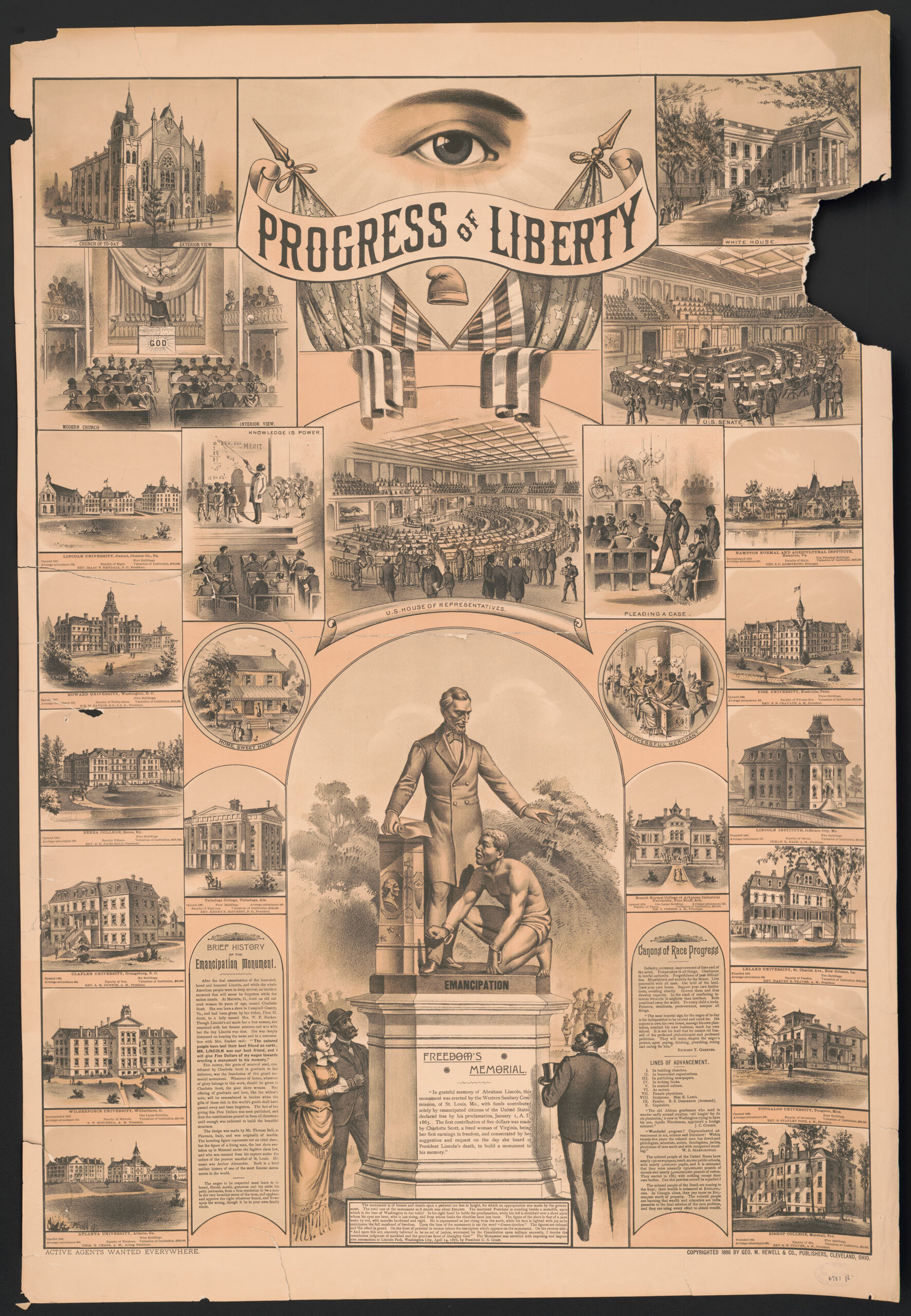

We might, then, speak of a burdened visibility. The figures in the photograph with which this article began, though apparently doing nothing except standing before a camera, carried this burden of proof (see Fig. 1). Even after slavery’s end, the bodies, families, homes, lands, and labor of those living on the Sea Islands were not entirely their own; all these things were charged with displaying the legacy of enslavement, the effects of emancipation, and the conduct and character of Black life. An 1886 chromolithograph celebrating the “Progress of Liberty” since emancipation literalizes this ocular scrutiny, placing vignettes of Black colleges and churches, commerce and Congressional representation, under the all-seeing Eye of Providence (Fig. 8).21 The eye, though a religious and civic symbol, here takes on a human, eerily anatomical form as, unmistakably, a white person’s eye. And as the vignette of “Home, Sweet Home” on the left side of the chromolithograph suggests, the private spaces constituted by the freedpeople’s families and households were among the sites at which they were most insistently subjected to observation. Alvord, for instance, assumed his right to oversee the private, indeed the interior, lives of the freedpeople of the Sea Islands when he wrote that they “compare favorably with other laboring classes in moral conduct, temperance, chastity, and especially in a desire for quiet home-life.”22

With similar presumptions of access, O’Sullivan hauled his stereograph camera, bottles of liquid collodion, glass plates, and portable darkroom to the freedpeople’s doorsteps in 1862. Since the eighteenth century, the quarters allotted to enslaved people on South Carolina plantations had been geographically separated from the enslaver’s house, their cabins often clustered together along a street. These spaces, subject to both surveillance and neglect during the era of slavery, now suffered examination in the softer guise of humanitarian concern.23 O’Sullivan’s visit was likely only one of many endured by those who lived there, as Northern missionaries and teachers made it their business to inspect the homes of the freedpeople and instruct them in domesticity. Laura M. Towne, a teacher who arrived in 1862, described the freedpeople’s houses as dirty and disordered, disregarding the fact that the straitened living conditions of the enslaved represented the exploitative calculations of their enslavers.24 The physical plan of the enslaved household—here, what appear to be one- or two-room, single-story frame houses with gable-end brick chimneys, unglazed windows, clapboard siding, and shingled roofs—followed standard types on each plantation.25 On the Sea Islands, these structures usually housed two families in a space of around fourteen by twenty feet.26

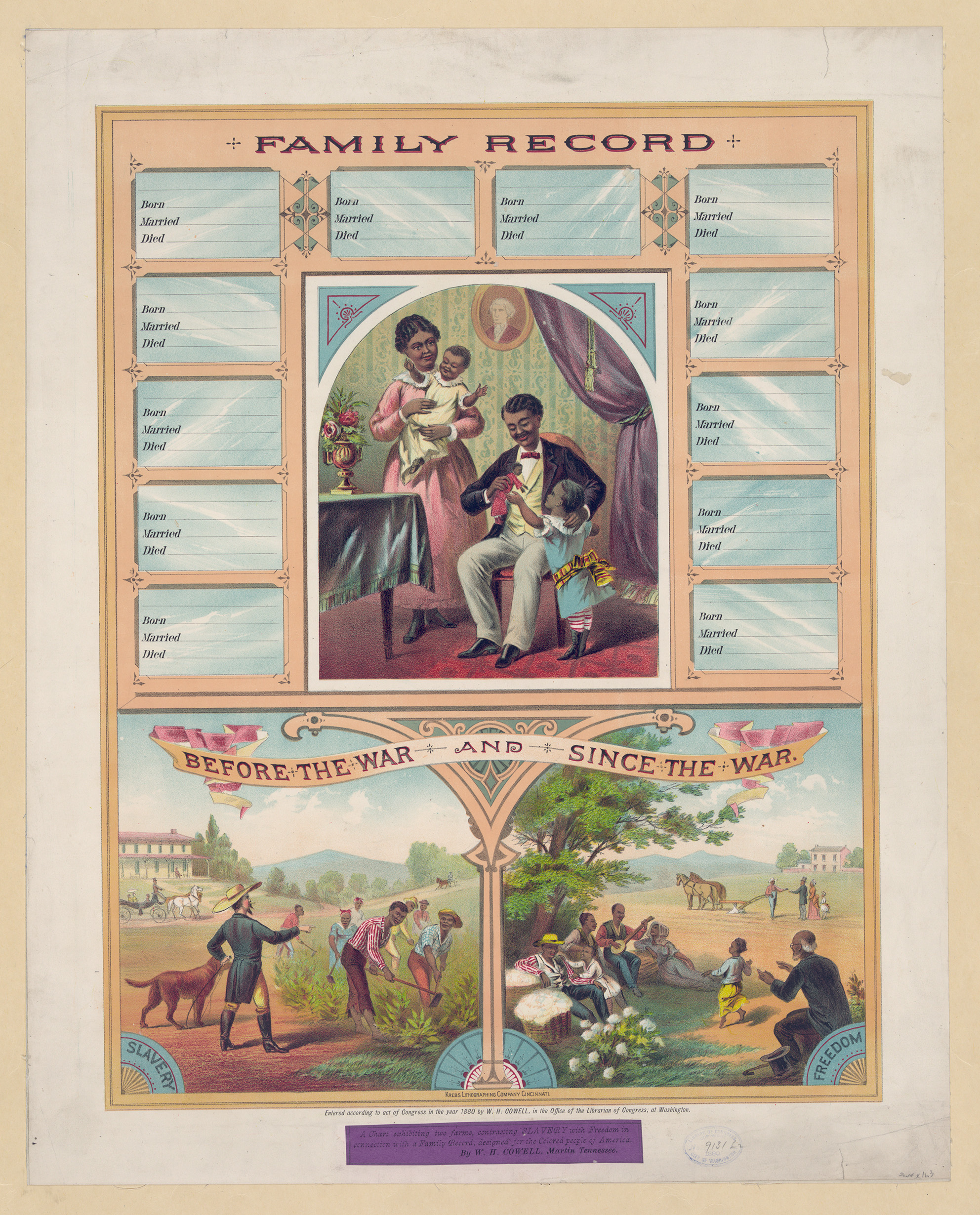

Not only the house, but the family within it was subject to a burdened visibility. Inconceivable as it might seem, given the efforts made by enslaved people to keep their kin together under bondage and reunite them after, a central anxiety of white officials and reformers in this period was enslavement’s undermining of the Black family. Much of this anxiety stemmed from these observers’ refusal to legitimate the non-nuclear structures of kinship that enslaved people had developed in response to “a long cycle of forced disruptions and reconstitutions of marriage and family life” by the sale of family members, violence both physical and sexual, and the upheavals of war.27 Efforts to impose the template of the nuclear family upon Black communities are evident in visual culture throughout the Reconstruction period. A chromolithograph “Family Record” published in 1880 and “designed for the Colored people of America,” for instance, shows a well-dressed husband and wife with two children in a snug parlor, with surrounding blank spaces to write in vital dates (Fig. 9). An ornate column elevates this vision of genteel domesticity above contrasting vignettes of life “Before the War” and “Since the War” (both of which, despite the putative opposition, seem to involve agricultural labor), exalting the middle-class family as the embodiment of liberation.

The O’Sullivan stereograph marketed to the public in 1862 under the title “Negro Family, Representing five generations, all born on the plantation of J.J. Smith, Beaufort, S.C.” offers a photographic instantiation of the family record (Fig. 10). The seated man in the center grasps his right wrist in his left, a gesture of bodily comportment and self-possession; the slightly outstretched arms of the central, standing man and the clasp of the seated woman on the elbow of the small child before her suggest familial bonds of care and responsibility. Yet both photograph and chromolithgraph are strange mixtures of the particularized and the generic. Where the chromolithograph family record is particularized in its text—intended for use by a family to record their own names and history—the photograph is generic, identifying the sitters only as a “Negro family” and giving the name of their former enslaver. Yet while the chromolithograph depicts a generic family scene, the photograph shows particular individuals, their embodied specificity at odds with the photograph’s caption. The title makes clear that this photograph was representative and typological, intended to demonstrate the condition of the Black family as a general category rather than to serve as a portrait of an identifiable group of related individuals.28 The photograph might have been made of this family, but the caption suggests it was not made for them. Still, O’Sullivan’s images of newly freed families arrayed in front of their homes implicitly refuse what Lisa Lowe describes as enslavement’s imposition of “exile” from “domesticity” and lay claim to the privileged kinds of legal and social personhood that such a possession conferred.29 Such complex dynamics reflect the family photograph’s importance as a highly contested, profoundly racialized site of postbellum politics.30

Like many family photographs, O’Sullivan’s “Negro family” reveals the household as a site wherein society’s racialized, classed, and gendered dynamics intersect in ways both obvious and unmarked.31 Though most of the people in the photograph are women and children, the figure at the apex of the composition is identifiably male. We cannot know whether the sitters, or photographer, or both, determined its arrangement, but the photograph signals the accession of Black men to leadership of family and community, a message that would have been reassuring to Northern officials and reformers who fretted that enslavement had weakened patriarchy within Black households.32 And though the family was a crucial site of “solidarity between African American men and women” in the face of white violence in this period, the status and protection it afforded to Black women did not guarantee their own civil rights.33 Federal officials in the emancipation era were constantly preoccupied with solemnizing formerly enslaved people’s marital relations, and thus, as Stephanie McCurry writes, with “transform[ing] enslaved women into wives.”34 Freed Black women were no longer subject to the power of enslavers, but as wives, subject to the laws of marriage, neither were they “endowed with the quality of self-possession.”35 While Black women advocated for their liberation and labored for the Union war effort, lawmakers did not view their freedom “as a human and natural right” earned by their service to the nation, as was true for enslaved men who served as soldiers.36

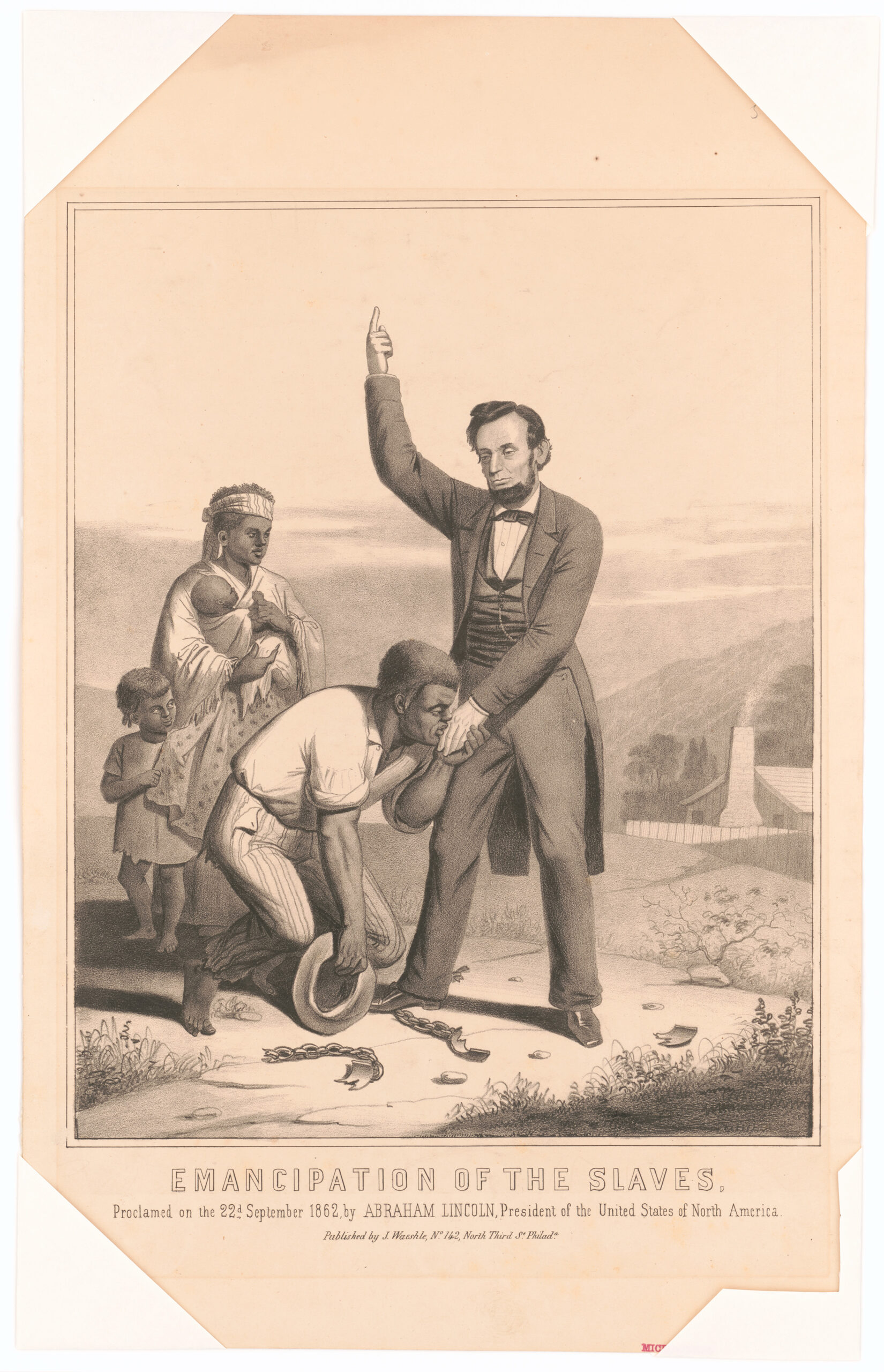

This complex interplay between gender, family, and freedom is visible everywhere in Reconstruction visual culture, not only in photography, but also in popular prints such as the lithograph “Emancipation of the Slaves,” published the same year O’Sullivan visited Port Royal (Fig. 11). The print might almost have been intended as a diagram of the interlocking hierarchies of race and gender in the nineteenth-century United States. The Black male figure serves as the compositional link between Lincoln’s liberating gesture and the Black woman and children, the conduit through which their freedom is realized. As Amy Dru Stanley has observed of the divergent meanings of emancipation for Black women and men: “Her freedom represented something owed to him.”37 Smoke drifting from the chimney in the background suggests the hearth tended within, reinscribing the domestic as the site where freedom would be most properly enjoyed—but in which, as we have seen, freedom would be experienced in profoundly different ways by various members of the family.

As this image of a salvific Lincoln suggests, even those white Americans who celebrated emancipation often conceived of it in deeply paternalistic terms. General T.W. Sherman, whose troops had driven the Confederate defenders from the Sea Islands, wrote in January 1862 about the freedpeople in his theater: “[B]efore they can be left entirely to their own government they must be trained and instructed into a knowledge of personal responsibility” and “civilization.”38 We see such assumptions at work in one of the more disquieting images from O’Sullivan’s Sea Islands visit: a strange scene of martial domesticity (Fig. 12). Seven white men sit around a table laden with wine bottles, a dish of bread, a soup tureen, and a silver coffee pot: the epitome of a certain kind of refinement, of “civilization” in the wilderness. Two of the men wear Union Army uniforms with officers’ shoulder straps; the others are in dark suits. Two young Black men, one in a Union cap and coat, the other in a plain jacket, stand to either side of the table; a young Black woman in a lacy dress or blouse stands behind it. The three young adults appear to be waiting on the seated diners. Captioned “Our Mess” by Brady in 1862 and Gardner in 1863, apparently referring facetiously to a soldiers’ mess hall, the image crystallizes the hierarchies that remained within the nation’s house. To contemporary eyes, the photograph makes clear a relation of dependence, but not the one that white Northerners imagined in 1862. The photograph shows how much of what Sherman might have meant by “civilization”—dining room and parlor, fine clothes and elegant objects, ease and comfort—depended, and continued to depend, on the exploited labor of Black men, women, and children. O’Sullivan’s “Negro Family” and “Our Mess,” then, stand not as clear evidence of the “Freedmen’s condition,” but as ambivalent, even contradictory reflections on what freedom as a condition meant in the Sea Islands in 1862.

Histories, Geographies, and Grounds

Brady and Gardner marketed “Negro Family” and “Our Mess” as “Groups,” suggesting that the subject matter of the images was the human figures within them.39 But compositionally, both photographs direct the viewer’s gaze to the land itself. The deictic gesture of the child touching the earth in the foreground of the family portrait and the claustrophobic crowding of grass and leaves around the dinner table turn the viewer’s eyes away from the figures. The images invite the viewer to consider the freedpeople’s “condition” from the ground up, from the land and its history. Whether by design or accident, the images open themselves to what Sarah Elizabeth Lewis has called “groundwork.”40 Lewis poses a central question for examining any kind of landscape representation: “What happens when we interrogate the idea of ground not as a notional plane to which all have access, or as part of an earthen foundation beneath our feet, but as a diasporic site of struggle on stolen indigenous land?”41 O’Sullivan’s photographs make visible competing claims to the literal ground of the Sea Islands, claims rooted in histories of racialized conquest, extraction, and labor, their interweaving patterns as complex as those the tidal creeks cut through the land. These images manifest what Leslie A. Schwalm has termed the “situatedness of subjection,” the modes of power and disempowerment that operate in and through specific geographies.42And as Dana E. Byrd has argued, Reconstruction in the Sea Islands was above all a radical “transformation of space,” an attempted remaking of enslavement’s geography through the founding of new towns, construction of military infrastructure, and partition and sale of plantations.43

In 1862, emancipation had barely dawned, while the geography of enslavement on the Sea Islands had been shaped by over three hundred years of history. Before the sixteenth century, the land was home to the chieftaincies of the Guale and Cofitachequi and their allies, who lived in coastal towns and were related to the Southeastern nations later known to settlers as the Creek, Chickasaw, and Cherokee.44 Spanish colonists arrived in the area in 1525 and soon brought with them kidnapped and enslaved Africans, who were present in what would become South Carolina by 1526.45 British settlers followed in the seventeenth century, the most powerful and highly capitalized of them immigrating from the Caribbean, where a brutally extractive plantation economy was hungry for more land. The colony of “Carolina” was chartered in 1663 to a Barbadian planter and his aristocratic associates, who set about converting land into commodities: first, through the harvesting of timber, tar, and turpentine for naval stores, and later through the cultivation of indigo.46

To return to the image advertised by Brady and Gardner as “[r]epresenting five generations” born on a Beaufort plantation (see Fig. 10), this caption suggests the arrival of an enslaved ancestor in South Carolina sometime before 1800. The forebears, perhaps even the oldest members, of the family that O’Sullivan photographed in 1862 would have witnessed a profound change in the islands’ economy in the late eighteenth century: the coming of cotton. Seeds of long-staple cotton were imported from the Bahamas, first grown on Hilton Head Island in 1790, and thrived in the salt-licked, sandy soil found along the Georgia and South Carolina coast.47 Soon known as “sea island cotton,” this variety possessed “long, strong, and silky” fibers suited to the weaving of expensive muslins and laces.48 The profits to be made from the crop and the extremely labor-intensive nature of its cultivation meant that by 1860, enslaved people in the Beaufort District outnumbered whites by two to one.49 The vast Sea Island plantations were the “quintessence of large scale plantation economy”: dependent on the labor, skills, and knowledge of entire communities of enslaved people, for the benefit of a few powerful white families.50

O’Sullivan in 1862 trained his lens on the formerly enslaved, but he also documented the generational wealth and power of the men and women who had enslaved them. When taking the photograph captioned by Brady and Gardner as “Moss-covered tomb, over 150 years old, on Rhett’s plantation, Port Royal Island, S.C.” (Fig. 13), O’Sullivan stood on land that had once belonged to Robert Barnwell Rhett, a vitriolically proslavery secessionist and descendant of a planter dynasty built on rice and cotton.51 The burial place of an enslaver, settler, and planter family ties land to inheritance, to property relations structured by genealogy. Freedpeople understood and contested the role that burial played in claiming ground: at some plantations in South Carolina, the newly emancipated dug up the enslaving family’s graveyard and scattered the bones interred there.52 In this photograph, the tomb itself is almost invisible, lying in the shadow of a massive tree that dominates the composition. The moss-draped limbs and tomb together suggest a gothic vision of mortality, of the rot and decay that had struck down slavery’s aristocracy.

But the photograph is also capable of bearing a different interpretation in the context of Reconstruction-era contests over land ownership in the Sea Islands. When war and emancipation threatened the sacrality of property rights, white Southerners turned to a sentimental economy of ownership—a rhetoric given visual incarnation, whether or not he intended it, in O’Sullivan’s photograph. As one white South Carolinian lamented in 1870, the Sea Island planter families had been “so broken down by want and oppression as to be willing to abandon their homes and the homes of their ancestors; the tombs and sepulchres [sic] of those who have preceded them in life.”53 These claims, of course, rested on a highly selective reading of the words “home” and “ancestor.” A report sent from the Sea Islands to the Freedmen’s Bureau by Brevet Brigadier General William E. Strong in March 1866 noted that the freedpeople, too, “seem very much attached to the islands where they were born and raised, and it is useless to attempt to hire them to leave and work other plantations.”54 He added: “They very much prefer to remain at their old homes,” even when “they are unable to cultivate more than one quarter of an acre of land.”55 The families whom planters sought to dispossess had often inhabited the Sea Islands as long as their enslavers; their kin, too, were buried there.56 As one freedman remarked: “What’s [the] use of being free if you don’t own land enough to be buried in?”57

The Sea Islands and the adjacent South Carolina and Georgia coast experienced perhaps the most complicated, “intense and bitter” struggles over land to take place anywhere in the former Confederacy.58 After the Union Army occupied the area, the federal government deemed Sea Island plantations “abandoned lands” and confiscated them. When the government put the properties up for public auction in June 1863, many of the plantations were bought by Northern entrepreneurs eager to try cotton planting with so-called free labor.59 In January 1865, however, General William Tecumseh Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15, which designated much of the islands and coast for “the sole and exclusive management” of their emancipated inhabitants and Black refugees from elsewhere in the South. Sherman’s order, however, granted only “vouchers” and “possessory titles” to land, and to the fury of the freedpeople, President Andrew Johnson later rescinded the order and refused to recognize many of these claims. Some Sea Island land which the government had been using for military purposes was sold in plots to freedpeople between 1863 and 1870.60 But, as Strong’s 1866 report from the islands noted, since enslavement had denied them any opportunity to accumulate capital, it was almost impossible for the freedpeople to succeed as independent farmers, even where they did manage to acquire land. Strong wrote with frustration: “I do not think the freedmen will make very much of a crop this year…[I]f they were only provided with the means to [purchase] cotton seeds, mules, and farming implements, very many of them would do exceedingly well.”61 Thus in 1862 and the years that followed, the Sea Islands were a site of struggle over the rights of property, the claims of sentiment and memory, and the power of labor and capital.

Material History

Intimately tied to debates over land ownership on the Sea Islands were debates over the form and conditions of labor that ought to replace enslavement—a debate which pitted freedpeople against the Northern capitalists and federal officials who controlled most of the lands on the islands in the 1860s and the white Southerners who would eventually return. After the Confederate defeat in November 1861, Black workers burned many of the islands’ cotton gins and refused, to the ire of federal officials, to continue harvesting that autumn’s cotton, choosing instead to bring in their own subsistence crops to ensure their families would be fed through the winter.62 A December 1861 issue of Harper’s Weekly reflected this official displeasure in a page of racist illustrations entitled “Work’s Over,” which purported to show Beaufort freedpeople trading, gossiping, and dancing.63

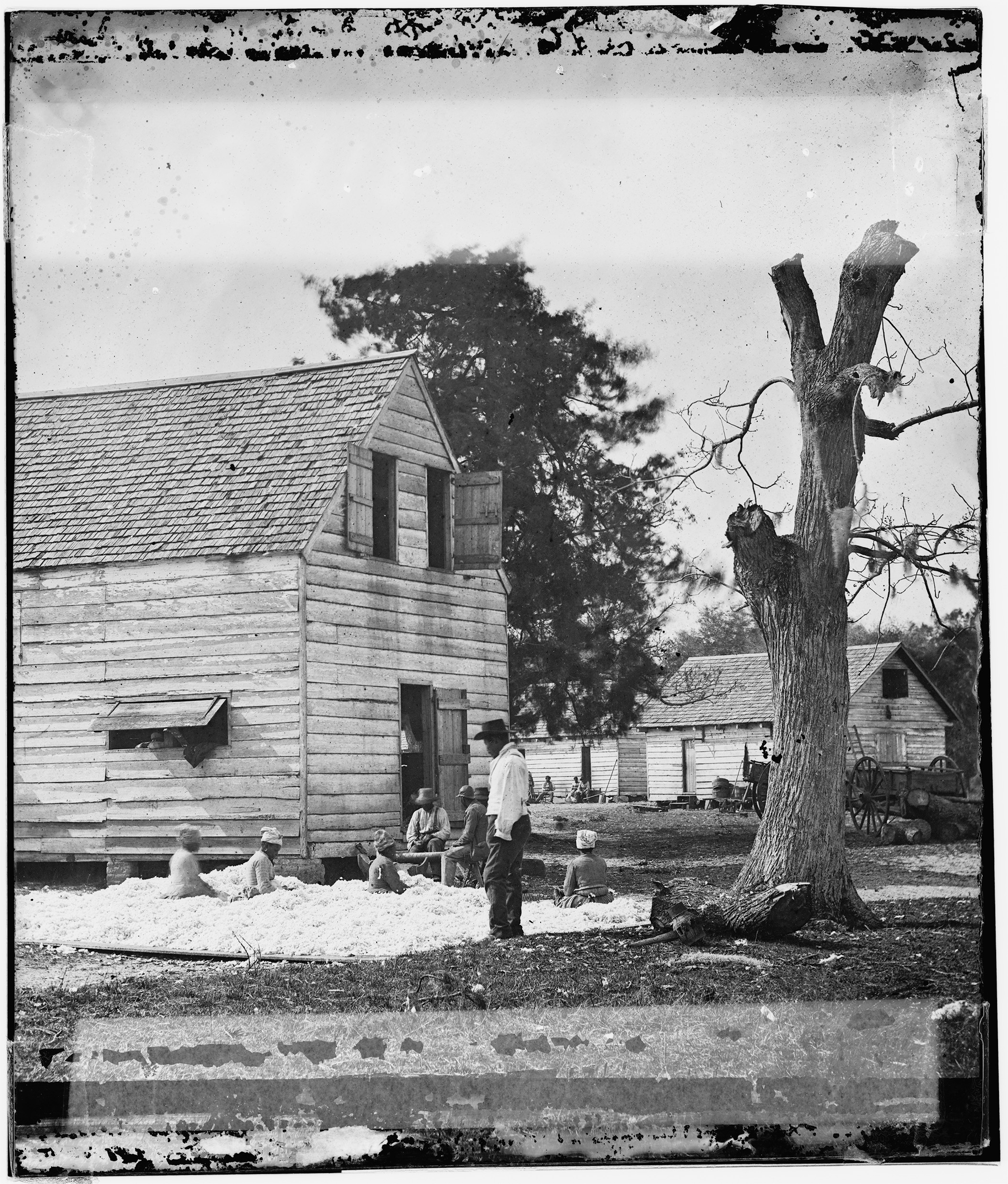

What, under such conditions, did images of Black labor in the Sea Islands signify? O’Sullivan took only one photograph of freedpeople at agricultural work (Fig. 14). He showed them processing cotton, despite the near-universal testimony of those who visited the islands that the freedpeople preferred to cultivate any crop other than that which had marked their enslavement. As Laura Towne remarked in 1862, the freedpeople “can see clearly enough that the proceeds of the cotton will never get into black pockets.”64 O’Sullivan’s image shows women seated amid a dense cloud of cotton, preparing it for the gin. As Anna Arabindan-Kesson has observed in an eloquent reading of this image, the cotton piled up to their waists seems to cling to the women, to weigh down their bodies and bind them to the ground. They are, she writes, “submerged in cotton.”65 What has gone unremarked about this photograph is the fact that, if we follow Sarah Lewis’s call to dig into the ground of representation, we find that the material basis of the image is, in part, cotton.66 While most histories of the plantation South focus on the importance of cotton textiles in driving enslavement and industry, O’Sullivan’s negative contains cotton in the form of a chemical product: guncotton. The substance that sticks so tenaciously to the bodies of the women in the photograph is also the chemical substrate that fixes their image to the glass plate (Fig. 15).

The method by which O’Sullivan made these negatives is known as the wet-plate collodion process, the most widely used photographic process between its invention in 1851 and the introduction of gelatin dry plate in 1871.67 Making a wet-plate negative involved coating a glass surface in light-sensitive liquid collodion and exposing the plate while the collodion remained wet, hence the name.68 Collodion is formed by dissolving nitrocellulose, also known as guncotton, in ether and alcohol. Guncotton, a fluffy white substance as explosive as dynamite, results from the exposure of cotton—in the nineteenth century, this was usually a by-product of cotton textile production known as “weaver’s waste”—to nitric and sulfuric acids.69 The syrupy collodion ground which fixed these evanescent images to the glass plate is composed of cotton fibers, chemically dissolved and transformed. The consumption of cotton in the manufacture of photographic chemicals was small compared to the overall market for textiles, and the cotton used in industrial chemicals would not have been the high-priced long staple produced on the Sea Islands. But the cotton plantation and the history of photography are nevertheless bound together, laminated to each other like collodion to a glass plate. The white heap of cotton in the O’Sullivan negative registers as a dark blotch, an occlusion in the visual field, but it was the chemistry of cotton that allowed the image to become visible at all.

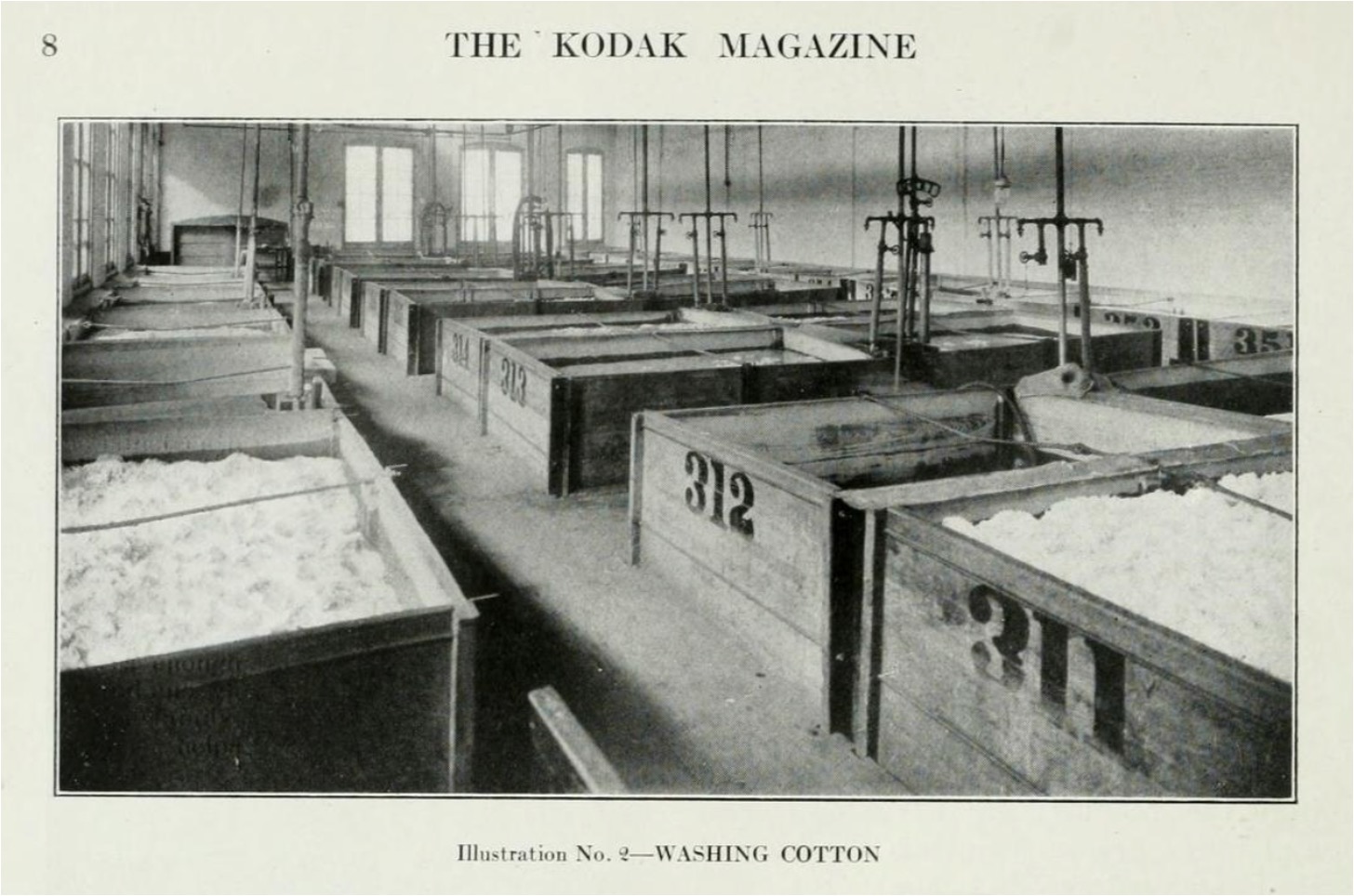

We understand the photographic image as capturing the past, yet the chemical materiality of these negatives calls us to engage in a different kind of historical analysis, akin to what might be termed “excavating the future.”70 Where history leaves its trace in the image, the future might be discernible in it as a kind of latency. Such excavations require close attention to the photograph not only as an image but also as an object, not only a visual but also a material, chemical thing.71 Despite many developments in photographic technology, cotton-derived chemicals remained crucial to the industry into the twentieth century and continued to shape the economic geography of the South.72 In 1920, the Kodak Magazine, Eastman Kodak’s corporate monthly, described the key materials for manufacturing photographic film: in addition to silver to form light-sensitive silver halides, the process required “bales and bales of cotton” for roll film’s celluloid backing (Fig. 16).73 As the corporation’s anonymous writer concluded, “A darky in the cotton field today may be…pulling the cotton for his next season’s shirt, or for a motion picture film he will later see produced when he goes to town.”74 Kodak’s text makes clear that photographs and films depended upon the racialized land and labor exploitation that subtended cotton production in the South long after Reconstruction. Though headquartered in Rochester, New York, Kodak located much of its chemical production in the South, at Tennessee Eastman in Kingsport, Tennessee, where cheap labor and ready access to cotton and timber supplied the photographic giant with cellulose-based chemicals.

The post-Reconstruction history of the Sea Islands reveals a different but related entanglement of cotton and chemical industry. As Siobhan Angus has written, many antebellum plantations later became sites of chemical manufacturing, reproducing and intensifying patterns of harm to the Black communities around them.75 In the Sea Islands, the 1868 discovery of deposits of phosphate-rich marl, a chalky, carbonate clay used to manufacture fertilizer, led to the opening of the country’s first large-scale phosphate mines in Beaufort County.76 By 1885, South Carolina produced half of the world’s phosphate.77 Hastily assembled corporations solicited Northern capital to buy or lease land from the district’s planters, who themselves depended on fertilizers to sustain cotton production, which exhausted the soil more quickly than did almost any other commodity crop.78 Industry boosters promised that phosphate would revitalize Southern agriculture.79 And indeed, large-scale agriculture’s need for fertilizer sources such as marl and guano drove imperial projects throughout the nineteenth century.80

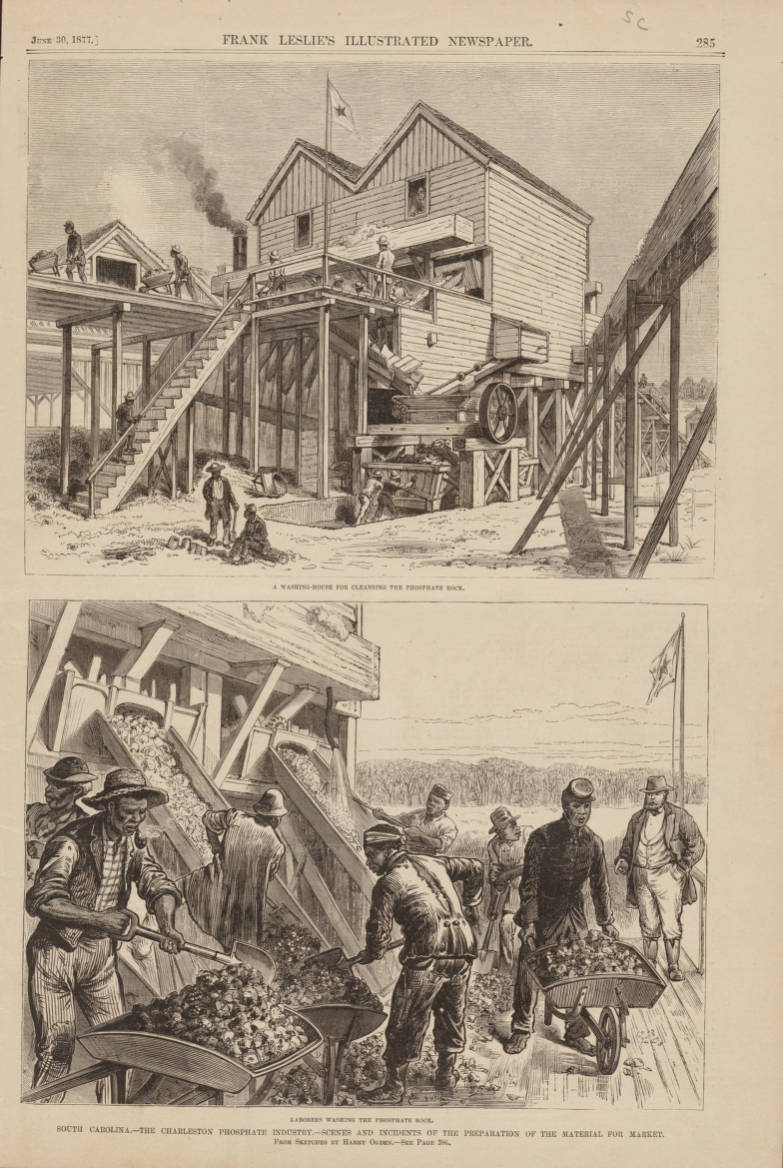

Thus timber and turpentine had given way to indigo, indigo to cotton, and now cotton to phosphate. Almost all the workers in the phosphate mines and processing plants were Black, many of them born into enslavement or the descendants of slaves. The phosphate mines leased incarcerated people, most of whom were also Black, from the state penitentiary, a form of forced labor that has been termed “slavery by another name.”81 The mines were largely unmechanized, and phosphate processing exposed workers to a variety of toxins, in addition to radioactivity from uranium present in the marl.82 When Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper carried an article on South Carolina phosphate mining in 1877—the year following the violent overthrow of the state’s integrated Reconstruction government by white supremacists—the accompanying illustration depicted a Black laborer bent over a barrow of phosphate rock, wearing a Union forage cap and uniform jacket, as if to mock the war’s broken promise of emancipation from such toil (Fig. 17). Though the phosphate industry collapsed in the 1890s and the profitability of sea island cotton continued to decline throughout the late nineteenth century, the extractive land and labor relations that had subtended the region’s plantations persisted.

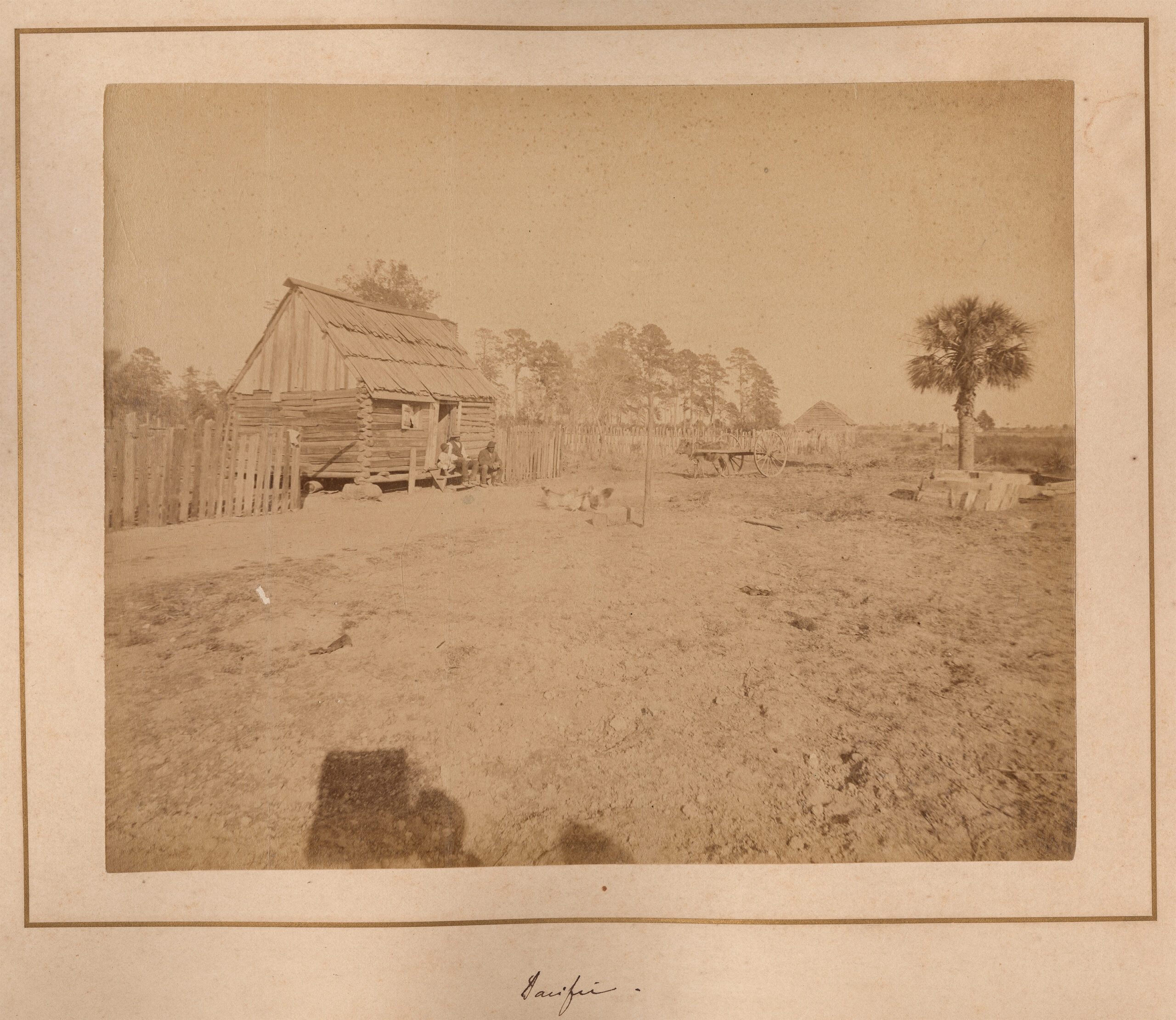

The phosphate industry brought another wave of outsiders to the Sea Islands, long after most of the reformers, missionaries, and teachers of the Reconstruction era had departed. Conrad Munro Donner, a white engineer for the Pacific Guano Company, which opened phosphate mines and a processing plant on Chisolm Island, just north of Beaufort, made a series of photographs of the region between 1889 and 1895.83 Unlike O’Sullivan, Donner was an amateur, his use of photography made possible by the rapid expansion of the photographic industry in the late nineteenth century. Among the engineer’s many images of workers, families, and homes in the Sea Islands is a photograph of two men and a child seated on the steps of a house, taken, like the O’Sullivan photograph with which this article began, from a distance (Fig. 18). Donner’s photograph, made some thirty years later, is marked by the same uneasy combination of white gaze and Black subjects, of domesticity and instrusion, set in a landscape contoured by the afterlife of slavery. The shadows of photographer and camera at the bottom of the scene register the same preoccupation with seeing the condition of Black Southerners, with subjecting their everyday world to ocular inspection and visual documentation. The ground seems to swallow up much of the image: an expanse of sandy soil bearing the layered histories of plantation, homestead, mine, and factory, of cotton and chemicals. While O’Sullivan’s photograph was made at a moment of historical possibility—a moment in which the new terms of social, political, and economic life after emancipation had not yet been firmly established—the later image suggests the persistence of racial capitalism and its attendant ways of seeing both land and people.

Conclusion

What would it mean to narrate history in the negative? To accord as much weight to those things that did not happen, as to those that did? Such an inquiry would challenge many histories of the Reconstruction era, for it might lead us away from narratives of progress or failure to a more ambivalent consideration of abrogated freedoms, foreclosed futures, revolutions turned back, and apertures of possibility closed. In their visual indeterminacy, political ambivalence, and material complexity, O’Sullivan’s photographs of the Sea Islands invite such a perspective. These images both document the dawn of freedom and reflect relations of power and visibility that endured past the end of slavery. And in a material sense, the cotton-derived chemical substrate of the negatives links the history of photography, the plantation, and its afterlives.

Notes

1. The erratic captioning practices of Civil War photographers and publishers mean that we do not know whether O’Sullivan, Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, or E. & H.T. Anthony titled this photograph. Based on the surviving information on the negative sleeve, this image may have been offered for sale to the public by Brady and Anthony in 1862 under the title “View on Mills’ Plantation, Port Royal Island.” However, in 1863, Gardner listed an O’Sullivan stereograph from this set for sale titled “Negro Quarters, Smith’s Plantation, Port Royal Island, South Carolina,” which seems to correspond more closely to the subject. The negative’s Library of Congress title, “Port Royal, South Carolina. Slaves quarters,” reflects this uncertainty about the precise location. See “Brady’s Photographic Views of the War,” in Catalogue of Card Photographs Published and Sold by E. & H.T. Anthony, 501 Broadway ([New York: E. & H.T. Anthony,] 1862), 13-14, and Alexander Gardner, Catalogue of Photographic Incidents of the War, From the Gallery of Alexander Gardner, Photographer to the Army of the Potomac (Washington, D.C.: H. Polkinhorn, 1863), 10.

2. A note on capitalization: in recent years, scholars have taken a variety of approaches to the capitalization of the terms black/Black and white/White. I have chosen here to capitalize Black, a term that acknowledges a group of people of diverse ethnic, cultural, and kinship backgrounds, many of whom were brought to the Americas through enslavement and other forms of racialized violence. I have left white uncapitalized. Blackness represents a shared culture, identity, and community in which many take pride. Whiteness, when mobilized in similar ways, risks underwriting white supremacist and white nationalist ideologies. However, this debate is ongoing in the field of art history and in public discourse more broadly.

3. The term “contraband of war” was first used to provide a legal justification for refusing to return enslaved people to their former owners by General Benjamin F. Butler, when these self-emancipating people began crossing to Union lines at Fort Monroe, Virginia, in 1861. As Kate Masur has noted, “contraband” followed enslavement’s principles in treating people as property—here, property that could be confiscated and put to use in the Union war effort—but such a designation constituted the first tentative step toward emancipation. See Masur, “‘A Rare Phenomenon of Philological Vegetation’: The Word ‘Contraband’ and the Meanings of Emancipation in the United States,” Journal of American History 93, no. 4 (March 2007): 1050-84.

4. J.W. Alvord, Letters from the South, Relating to the Condition of Freedmen, Addressed to Major General O.O. Howard (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1870), 8. The Freedmen’s Bureau was the federal agency charged with providing food, clothing, medical care, schools, and other necessities to the formerly enslaved.

5. Library of Congress, “Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints,” https://www.loc.gov/collections/civil-war-glass-negatives/about-this-collection/.

6. Ibid.

7. Geoffrey Batchen, Negative/Positive (London: Routledge, 2020), 3.

8. Tina M. Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 122.

9. Batchen, Negative/Positive, 3.

10. Campt, Image Matters, 127.

11. Jennifer Raab, Relics of War: The History of a Photograph (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024).

12. Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” The Atlantic (June 1859), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1859/06/the-stereoscope-and-the-stereograph/303361/.

13. On Holmes, race, and the negative, see Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, “Negative-Positive Truths,” Representations 113, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 16-38.

14. Catalogue of Card Photographs Published and Sold by E. & H.T. Anthony, 13-14, and Gardner, Catalogue of Photographic Incidents of the War, 10. The “Sherman” in Gardner’s catalogue refers to Union General T.W. Sherman, not the better known General William Tecumseh Sherman.

15. For an analysis of the Moore photographs, see Dana E. Byrd, with Tyler DeAngelis, “Tracing Transformations: Hilton Head Island’s Journey to Freedom, 1860-1865,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 14, no. 3 (Autumn 2015): https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn15/byrd-hilton-head-island-journey-to-freedom-1860-1865.

16. Nicholas Mirzoeff, “The Subject of Visual Culture,” in The Visual Culture Reader, ed. Mirzoeff, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2001), 10.

17. Ibid. Mirzoeff elsewhere describes the surveillance exercised on the plantation as the foundational exercise of “visuality,” or the assumption of the “exclusive claim to be able to look.” Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 2.

18. Ilisa Barbash, Molly Rogers, and Deborah Willis, eds., To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum Press, and New York: Aperture, 2020), and Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,” American Art 9, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 38-61.

19. Photography’s evidentiary capacities were also cited as the key to its potentially anti-racist politics, most famously by Frederick Douglass in his 1861 “Lecture on Pictures” in Boston’s Tremont Temple. See Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith, eds., Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012).

20. Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, rev. ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2022), 205-6.

21. Jasmine Nichole Cobb has described slavery itself as an “ocular” institution. See Cobb, “A Peculiarly ‘Ocular’ Institution,” in Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 28-65.

22. Alvord, Letters from the South, 14.

23. John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 155. For analysis of the specific organization of the Sea Island plantation, see Byrd, with DeAngelis, “Tracing Transformations.”

24. Laura M. Towne, Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne, Written from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, 1862-1884, ed. Rupert Sargent Holland (Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, 1912), 5.

25. Vlach, Back of the Big House, 160.

26. Byrd, with DeAngelis, “Tracing Transformations.”

27. Stephanie McCurry, Women’s War: Fighting and Surviving the American Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019), 85.

28. For the distinction between portrait and type, see Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,” American Art 9, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 38-61.

29. Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 18.

30. Sarah Parsons, “Domesticating Jefferson Davis: Family Photography and Postwar Confederate Visual Culture,” American Art 37, no. 1 (Spring 2023): 82-105; Shawn Michelle Smith, “‘Baby’s Picture is Always Treasured’: Eugenics and the Reproduction of Whiteness in the Family Photograph Album,” The Yale Journal of Criticism 11, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 197–220; Laura Wexler, Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of U.S. Imperialism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000); and Deborah Willis, ed., Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography (New York: New Press, 1994).

31. Wexler, Tender Violence, 6.

32. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 215.

33. Kirsten Pai Buick, Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 55. See also Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), Tera W. Hunter, To ’Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), and Martha S. Jones, All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

34. McCurry, Women’s War, 118.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. Amy Dru Stanley, “Instead of Waiting for the Thirteenth Amendment: The War Power, Slave Marriage, and Inviolate Human Rights,” American Historical Review 115, no. 3 (June 2010): 760.

38. The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series I, volume VI, no. 6 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899), 128.

39. Catalogue of Card Photographs Published and Sold by E. & H.T. Anthony, 13-14, and Gardner, Catalogue of Photographic Incidents of the War, 10.

40. Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, “The Arena of Suspension: Carrie Mae Weems, Bryan Stevenson, and the ‘Ground’ in the Stand Your Ground Law Era,” Law & Literature 33, no. 3 (2021): 487-518, and Lewis, “Groundwork: Race and Aesthetics in the Era of Stand Your Ground Law,” Art Journal 79, no. 4 (October 2020): 92-113.

41. Lewis, “The Arena of Suspension,” 488.

42. Leslie A. Schwalm, Emancipation’s Diaspora: Race and Reconstruction in the Upper Midwest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 1.

43. Byrd, with DeAngelis, “Tracing Transformations.”

44. Lawrence S. Rowland, Alexander Moore, and George C. Rogers, Jr., The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: 1514-1861 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2020), 10.

45. Rowland, Moore, and Rogers, The History of Beaufort County, 18.

46. Guion Griffis Johnson, A Social History of the Sea Islands, with Special Reference to St. Helena Island, South Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1930), 17-21.

47. Johnson, A Social History of the Sea Islands, 23.

48. Johnson, A Social History of the Sea Islands, 24. For the uses of long-staple cotton, see Johnson, 29.

49. Johnson, A Social History of the Sea Islands, 38.

50. Johnson, A Social History of the Sea Islands, 27.

51. Rowland, Moore, and Rogers, The History of Beaufort County, 280.

52. Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, updated ed. (New York: Harper Perennial Classics, 2014), 71.

53. Richard DeTreville, Sea Island Lands. St. Helena Parish and Its Citizens. A Few Chapters from a Faithful Unpublished History of the War of Secession (N.p.: unknown publisher, 1870[?]), 15.

54. Report from William E. Strong, March 1866; Synopses of Letters and Reports Relating to Conditions of Freedmen and Bureau Activities in the States, January 1866–March 1869; vol. 1, p. 121; War Department, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, Office of the Commissioner, 1865-1872; Record Group 105; National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.

55. Ibid.

56. Lowe, Intimacies of Four Continents, 21.

57. Douglas R. Egerton, The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America’s Most Progressive Era (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 92.

58. Egerton, Wars of Reconstruction, 108.

59. Foner, Reconstruction, 69.

60. Johnson, A Social History of the Sea Islands, 187.

61. Report from William E. Strong, p. 121.

62. Foner, Reconstruction, 51.

63. “Work’s Over,” Harper’s Weekly 5, no. 260 (December 21, 1861): 805. I have chosen not to reproduce these racist images.

64. Towne, Letters and Diary, 20.

65. Anna Arabindan-Kesson, Black Bodies, White Gold: Art, Cotton, and Commerce in the Atlantic World (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 129

66. Lewis, “Groundwork,” 94.

67. Sarah Kennel, with Diane Waggoner and Alice Carver-Kubik, In the Darkroom: An Illustrated Guide to Photographic Processes Before the Digital Age (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, and New York: Thames & Hudson, 2009), 25.

68. Ibid.

69. Kennel, In the Darkroom, 81. For “weaver’s waste,” see Karl Rohrer, “Gun-Cotton: Its History, Manufacture, Use,” Scientific American 60, no. 8 (February 23, 1889): 116.

70. Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, new ed. (London: Verso, 2018).

71. See, for materials analysis in photography studies, Siobhan Angus, Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography (Durham: Duke University Press, 2024).

72. I am indebted to Siobhan Angus for a generative series of conversations about the chemical uses of cotton.

73. “How Kodak Film Is Made,” Kodak Magazine 1, no. 5 (October 1920): 7.

74. Ibid.

75. Siobhan Angus, “Chemical Necromancy: Plantations and Petrochemical Refining in Cancer Alley,” liquid blackness: journal of aesthetics and black studies (forthcoming 2024).

76. Kristina A. Shuler and Ralph Bailey, Jr., “A History of Phosphate Mining Industry in the South Carolina Lowcountry,” South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office (2004), 11.

77. Shuler and Bailey, “A History of Phosphate Mining Industry,” 40.

78. Brian Williams and Jayson Maurice Porter, “Cotton, Whiteness, and Other Poisons,” Environmental Humanities 14, no. 3 (November 2022): 499-500, 504.

79. Williams and Porter, “Cotton, Whiteness, and Other Poisons,” 508.

80. Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (New York: Picador, 2019), 46-58.

81. Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery By Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2008).

82. Shuler and Bailey, “A History of Phosphate Mining Industry,” 31-2.

83. “Phosphate, Farms & Family: The Donner Collection,” Beaufort County Library, South Carolina Digital Library, https://scmemory.org/collection/phosphate-farms-family-the-donner-collection/.